Travis Weller. Photo credit: Bill McCullough

Travis Weller is a native Texan composer, performer and instrument builder. He founded Austin New Music Co-op, which has been presenting adventurous new music in central Texas since 2002. His music has been commissioned and performed by ensembles in Europe and cities across the US. Travis collaborates frequently with a large group of colleagues, both regional and international, and has worked in residence at Cornell University, The Contemporary Austin, The University of Texas, STEIM in Amsterdam, The Blanton Art Museum, Berkeley Art Museum, and the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston.

Odyssey Works: What are you trying to do with your work?

Travis Weller: I'm going to be frank here and say that I really don't know what the heck I'm doing. Every new project is interesting to me because of that. When you work in a discipline long enough, I think there can be a tendency to become more efficient. To figure out what works and do it faster. Time equals money, right? But I've found too much profound beauty by ignoring that equation. Exhaustive exploration of a possibly dumb idea. Enshrinement of the mundane. Or as John Cage said: "If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all."

OW: How does your art practice influence your life?

TW: I often wish I was the type of person who got up every morning at 6 a.m., swam a mile at Barton Springs, had a healthy breakfast and then sat down in a well lit room using good posture and composed music until lunch time. But I am not that guy. My art practice consists of biting off more than I can chew and running to a date. As a result, my art practice puts the brakes on just about everything else in my life two weeks prior to a deadline. Sad but true.

OW: You do a lot of diagramming, and a score is a kind of diagram. Can you talk about how to think about diagramming as a compositional tool?

TW: I honestly can't remember a time when I didn't make diagrams for things. For me, it has always been a way to understand a problem or a concept or a sequence of ideas. I use diagrams for composing music, but I've also used them for yard work. They help me get a sense of what is and isn't important in the task at hand. They help me work on many levels at once by allowing an essential amount of detail while still keeping the overall big picture in view. In music, this is vital. If you don't have both, the piece falls apart. I can't keep all the parts of a score in my head at once. That isn't how it works for me. But details and sequence are immensely important in music, or any time-based art really. Of course, for me the overall form is also a key factor in the success of a piece. By using a series of diagrams, I'm able to work within a formal structure while adding the important details until the piece emerges for me. I really can't imagine doing it any other way.

“If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.”

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience in which art changed you?

TW: I have too many influences to list so but for the purposes of this question, I'm going to stick with a handful of composers that have had a major impact on my work -- The New York School composers John Cage, Morton Feldman, Earle Brown and Christian Wolff. Coming from a mostly classical background, they really changed my essential ideas about what music is, and why it is important. On one level, studying their writings and scores widened my thinking, but that wasn't the magic moment. It wasn't until I was immersed in a three day festival playing a ton of different pieces by each of the four composers that everything really clicked for me. It was something about being so close to the music made by these four guys, who were all friends and colleagues, and understanding on a really visceral level how their music fits together. As the project came together, with these crazy performances, it was a real watershed moment for me.

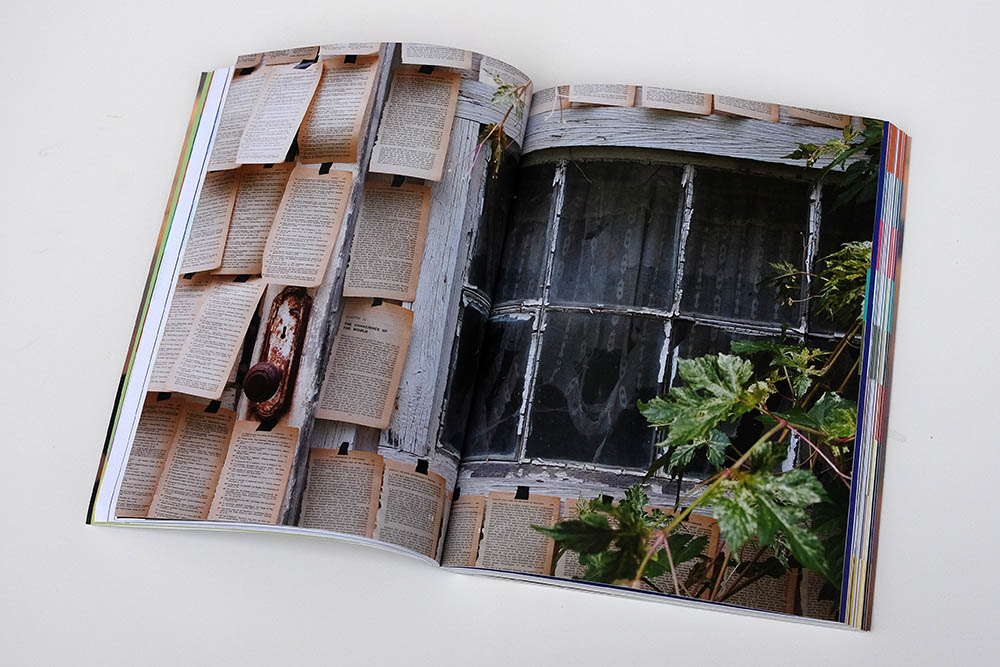

Photograph by Elizabeth Shear

OW: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

TW: From a musical standpoint, I'm a believer in live performances. Recordings are a huge part of our musical lives, but there is something amazing and unique about being in the same room with a performer playing an acoustic instrument. There is an intimacy that is really clear to both the musician and the listener. I'm acutely aware of this when I compare my experience listening to a recording vs. listening to a concert. And as a performer, rehearsal has a totally different feeling from performance. I believe those two aspects act as a kind of feedback loop reinforcing one another. That experience when everyone is in the room together hearing sounds radiating through the air from vibrating instruments and bouncing off walls and floors in impossibly complex ways and making their way through ears to a bunch of brains which all have their own unique take on what just happened. That is where the art is.

OW: People, I think, are often scared by experimental music. How do you see comfort and discomfort as a part of the work you do?

TW: Over the past several years, I've been on a bit of a kick for 1960s middle of the road easy listening. I could go on and on about why I find it appealing, but its most striking quality is that it asks almost nothing of me a listener -- it only seeks to give. It's like a hypothetical acquaintance, let's call him Steve. When you're with Steve, he asks you lots of nice questions: "Hey, what cute thing is your kid doing lately?" "Did you get any good veggies out of that garden you worked so hard on?" Those afternoons at the coffee shop with Steve are so nice. Well, my favorite experimental music is less like Steve and more like Aldus, the shut-in down the street with Asperger Syndrome who dug a basement under his house and is down there doing DIY cold fusion experiments. Not exactly the kind of person you ask to take care of your cat while you're out of town -- but pretty goddamn interesting -- as long as you have the nerve to follow him into the basement to see what he's up to. It's not for everyone.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.