Albert Kong

Albert Kong is an artist designing live games and experiences in the Bay Area. His work is focused on the audience as a player, and the world as an unbounded space of play: site specific installations that ask players to view the physical and social space around through the lens of a new set of rules. He has presented at various festivals including IndieCade and Come Out & Play.

“I like to empower people in small, personal ways, showing how even minute intentions can affect the world.”

Odyssey Works: You've worked on escape the room games, Odyssey Works (developing the Beautiful Experience Design Workshop), The Headlands Gamble, The Vespertine Circus and just about every other underground and theatrical immersive and interactive endeavor in the SF Bay Area. Through all that, how do you understand immersivity and interactivity? What is the point?

Albert Kong: What is the point? The words “immersive” and “interactive” are often used so broadly that they serve as containers for anything that is new, designed, and even slightly participatory; they feel almost empty to me when they are used to describe new work after the fact. But as an aspirational quality for works, and when audiences are excited to find work that is immersive or interactive, I think it at least partially represents some collective cultural needs: ownership and reclamation of space; empowerment to engage; permission to play, permission to explore.

Come Out & Play Festival, credit Anna Vignet

When I was in elementary school, we had an amazing wooden play structure that we would climb all over during our breaks. I remember feeling disappointed when we continued onto middle school, and the only available play spaces were sports fields and courts. I would keep seeking out playgrounds until a few years later when I began to practice parkour, a community that specifically encouraged the exploration of space for alternative functions. For the next decade I practiced scanning the environment around me for the techniques that they afforded rather than the limitations that they represented. A wall is not a barrier but a structure to climb, a platform to stand on, a space to walk. That perspective also revealed that we are limited by rules we implicitly set for ourselves often more than any absolutes (why not stand on that bench? why not dance across the crosswalk?).

Games and embodied play--the terms I use for “immersives” and “interactives”--are a revealing form in that same way. They give permission to the audience to step out of their seats; they reward those who explore; they invite people to be a part of a world rather than voyeuristically peering into one. The games that excite me the most--experiences like Odyssey Works, Headlands Gamble, Journey to the End of the Night--appropriate the spaces that we exist in every day, inviting us to do what we would usually avoid in order to maintain the temporary world that the game creates.

I think the point is to remind individuals that we own our bodies and our actions no matter who “owns” the land we stand on, and to empower players to continue exploring the space that they occupy. (With the usual caveats of not causing harm to others, etc.)

OW: Why create experiences?

Ambulist, credit Danielle Pena

AK: As a game designer I often see an expectation from players for embedded narrative, for a story to be written and delivered throughout the experience of a piece, especially in realms connected with entertainment media--video games; escape rooms; alternate reality games. While I have a lot of respect for authored narratives, in designing experiences, I think there is a unique opportunity to introduce, influence, initiate personal narratives. The rules of a game can introduce a sense of uncertainty, a drama that can be more exciting than anything narrative that is written for them--sliding into the finish line in the nick of time, or suddenly realizing you’ve stepped into your opponent’s territory. The rules we follow for a game can overpower our perception of our own abilities; in Beacon, a chase street game I designed I was delighted to hear about a player who lept over a crowd, acrobatically kicking off a wall, in order to evade being caught. Playing a game can replace the rules and stories we associate with a space, a city, our lives; there are whole neighborhoods in the Bay Area that I associate with getting lost in the midst of Journey to the End of the Night, instead of as “cozy suburbs” or “boutique shopping districts.” I design experiences because I want to give people stories to tell from their own points of view.

OW: What is the role of wonder and discovery in what you do?

Climber Beta, credit Tobin Schwaiger-Hastanan

AK: I like to work in small magic. There’s the grand sense of revelatory wonder that one experiences when they are surrounded by the majesty of nature, and then there’s the realization that there really are bugs crawling underneath that rock. There’s the discovery that a simple equation can explain vast swaths of the physical world, and there’s the discovery that your friend was absolutely delighted when she received your impromptu letter. I like to empower people in small, personal ways, showing how even minute intentions can affect the world.

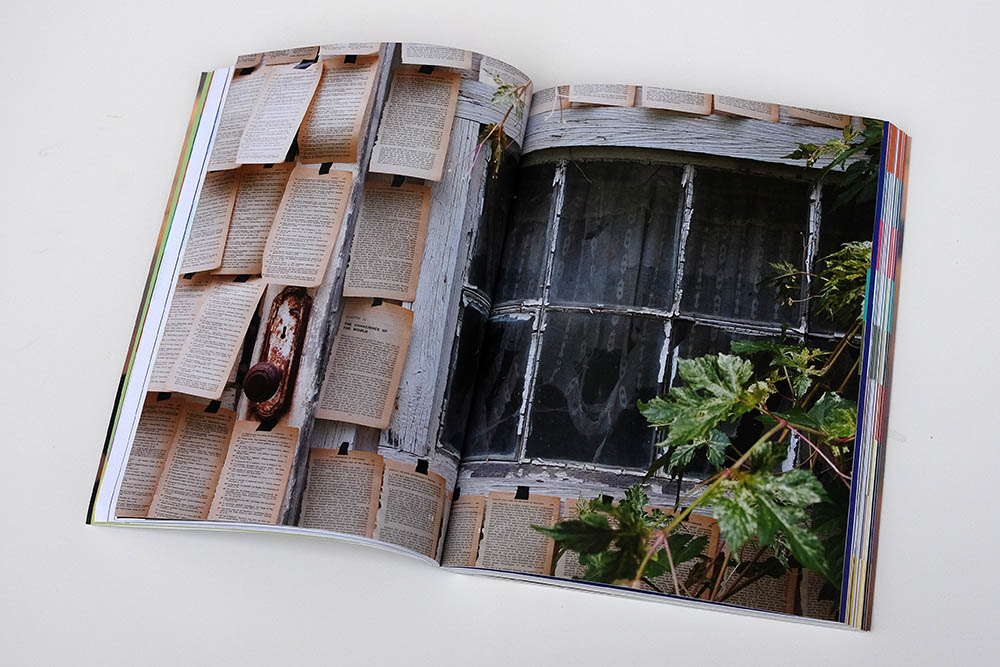

There’s a lot of wonder in the recognition that we are capable of so much more than we think we are, that the simple act of venturing to try—see if that doorknob turns; take that unfamiliar alleyway; enter that ancient-looking junk store—can lead us to magical adventures that we could scarcely imagine.

I think that’s a kind of magic that experience design is especially good at creating; we might behold a beautiful, ornately crafted piece of architecture in awe, but it doesn’t teach us that we ourselves, ordinary human beings, are capable of creation, art-making, affecting change, the way that even the smallest interaction can.

OW: How does your art practice influence your life?

AK: Making games and experiences allows me an alternative to cynicism, my default state perhaps as a result of my upbringing. Through my practice, I allow myself time to think carefully about the systems that govern our lives, the implicit laws and expectations, the cultural norms, the institutions in place; and where the state of these things would otherwise be pretty depressing, in art, I see solutions. I see opportunities to make these rules obvious by providing new rules. I imagine someone who goes through a game, or an Odyssey, or a designed adventure returning to the “real world” and questioning why shouldn’t I take the tag off this mattress; why should I drive to work when I enjoy biking more; who’s to tell me I can’t be an artist; what’s stopping me from making a difference in the lives of the people around me? I try to embody the states of mind that I try to share with those who play my games, and it’s honestly made me much happier.

Bring Home the Beacon, credit Lia Bualong

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience in which art changed you?

AK: This is two questions! I’ve been incredibly inspired by the work that came out of SF0, which bills itself as a collaborative production game, where players create tasks for each other that often involve real world interactions (climb a roof; modify a sign; take a bus to the end of the route). It was where Journey to the End of the Night was conceived, as well as the Wanderer’s Union and many others. I loved how it created community and participation through play. Along those lines, I’ve also been really inspired by the Nordic larp scene, fluxus event scores, the work of Nonchalance...

But you want me to pick one, right? I never thought of myself as an artist. I didn’t study it, I didn’t consider myself capable of making art; in my college years I hardly had a framework for understanding the work that I would see in museums, in books. But in one of those years I ran into Robert Yang, now a game designer and academic, then a student who was teaching a class on outdoor games. He was leading a handful of students through a game that was taking place around campus, with players smuggling objects over imaginary borders and evading imaginary guards. I didn’t know Robert at the time, but noticing some students running around with arm bands clearly up to some shenanigans, I stopped one of the players and asked them what was going on, and they directed me toward him, and he explained what was going on. The idea that a game like this was being orchestrated in broad daylight, in the middle of campus, with most of the students around us seemingly oblivious to what was going on, that was an epiphany. I had heard of and played some other games on campus--Assassins, Fugitive, Sardines--but this was the moment that made it a genre in my mind, rather than merely a random occurrence.

OW: What is the benefit of integrating multiple disciplines and how do you go about it?

AK: From a community/scene aspect, my background is in several new disciplines that emerge without a lot of background in the arts, and the recognition that other disciplines have a lot of solutions to the problems we face (how to maintain community, how to encourage new members, how to find satisfaction in art when there isn’t a commercial industry to support the medium) has been helpful. In the Bay Area game design scene we adopted an open mic model for sharing and testing new games that has been a really powerful way to make the medium more accessible to new designers.

Meanwhile, I personally am still learning and figuring out what art means; reading up, seeing more art, dipping my toes into new practices, and befriending other artists has been a way to sort of latently integrate new influences into my practice.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.