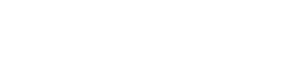

An image from OW 2014: The Dariad. Photo by Sasha Wizansky

What’s the longest time you have ever spent with a single piece of art?

When I visit museums, I often find myself spending an hour or more with just one piece of art. In my experience, it takes that long to really see it.

Looking at an artwork is a time-based experience; at first glance, it might come off as unassuming and quiet. After ten minutes, you start to notice things you didn’t before—new textures emerge, details become sharper, and colors become more vibrant. By thirty minutes, a piece has started to break through your shell and share its world with you. After an hour, you aren’t looking at the piece anymore; it is looking at you.

Being present, with an artwork no less, is a challenging feat in our modern world. But this is what artworks invite; this is the space they make in our lives, a space for presence. I am incredibly grateful for this.

With Thanksgiving right around the corner, I find myself reflecting on the many things that I am thankful for this year. 2015 has been a truly transformative year, due in no small part to my work with Odyssey Works. The group’s long-duration artworks have changed my perspective on the potential of art. Now I see so many possibilities that weren’t apparent to me before.

At the end of 2014, I received an incredible gift from the Odyssey Work crew: a surprise Odyssey. “The Dariad,” coordinated by Abraham Burickson and my dear friends in San Francisco, offered me the perfect avenue to explore ideas about art that I had been toying with for several years.

Outside of Odyssey Works, I'm a Medievalist, which means that I've spent the past several years studying centuries-old art and ways of seeing that art. The medieval way of seeing is both astounding and incredibly relevant even today. The Middle Ages have gotten a bad rap, going down in history as some sort of backwards-era that offers us nothing more than ugly pictures of baby Jesus. But the art of the period was about so much more than that.

Art from the Middle Ages is all about being present. You can’t see or experience the artwork if you aren’t really there. Medieval art requires patience, longing, and the viewer’s full-bodied participation.

In this way, medieval art theory speaks to and reveals new facets of modern performance artworks, such as that of Odyssey Works.

During the climactic scene of the Dariad, I met a group of around fifty wearing black outside of the De Young Museum in San Francisco. They had gathered for an unconventional tour of the museum, in which we would only view three pieces of art, but spend anywhere from 15-30 minutes with each individual piece.

As we stood in front of a modern-take on an aboriginal sculpture, and a large video installation by David Hockney, I was struck by the medieval-ness of the gathering. By standing in front of a single piece of art for a rather uncomfortable length of time, we had to honestly confront our feelings about a piece, and learn patience.

By engaging with the artworks for minutes, instead of mere seconds, we gave them the chance to look back at us.

During the Dariad, the final artwork that we viewed together as a group was Cornelia Parker’s Anti-Mass. This massive mobile-like piece consists of fragments of a former Baptist Church that had been destroyed by arsonists. The shards of wood are suspended in mid-air, offering a vision of extreme violence and a venue for quiet meditation in the same breath.

Standing in front of this artwork with fifty some people for thirty minutes was a surreal experience. I walked up close to the piece, sat on the bench in front of it, stood at the back of the gallery and waited for the piece to penetrate through my shell—the buffer that protects me, but also separates me from the rest of the world.

Minute by minute, I felt that protective layer dissolve. As every second wore on, I became more present.Anti-Mass crept deeper into my subconscious and altered my understanding of the world. Eventually, I watched my “self” melt away—I became a part of a collective consciousness in that room, communing with art.

Believe it or not, this communal experience is very medieval in its nature. The idea of the “I” emerged with the Renaissance, but the Middle Ages, on the other hand, demanded that egocentric I be subordinated to the collective we. This way of thinking about things may have been mostly lost to time, but in front of Cornelia Parker's work it was entirely accessible. This is the power of art. It transcends time and place; its message can permeate generations and outlast the lifespan of the artist who created it.

It is impossible to experience this and not be grateful.

The Dariad was just one transformative event that Odyssey Works offered me in the last year. Throughout 2015, I have been the acting Public Image Engineer for the group, which has allowed me to explore my creativity on a deeper level and be a key player in running the Kickstarter.

2015 has brought many blessings to the group, most important of which is the incredible outpouring of support that has come through our Kickstarter campaign. Even after months of planning and promoting, I find myself surprised by the fact that over 350 people have donated to the campaign, and that we met our goal after only 15 days!

Both of these wonderful gifts—the Dariad and the success of our Kickstarter—have demanded something important of me: to be present. To actually see the world and not take it for granted. To savor every moment with (or without) art. And to offer gratitude to a world that has blessed me so.

This Thanksgiving, I give thanks to all of you—the Odyssey Works supporters and volunteers that have worked to transform my life and the lives of other art enthusiasts for the better. Though our work might be small in scale, it’s monumental in its effects.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.