Have you ever wondered what it's like to be a participant in an odyssey works piece? This week we're pleased to introduce you to Sasha Wizansky, the recipient of an Odyssey in 2009. Since then we have had the great fortune to work with her as a designer on many an Odyssey Works project, including our Borges & Calvino forgeries, not to mention the design concepts for our forthcoming book.

Sasha Wizansky

Sasha Wizansky is an art director, graphic designer, and bookbinder, and holds an MFA in sculpture. Sasha co-founded Meatpaper, an award-winning, internationally distributed quarterly journal of art and ideas about meat, in 2007, and was Editor-in-chief and Art Director until the last issue came out in fall, 2013. Meatpaper’s mission was to create a non-dogmatic forum in which to explore the ethics, aesthetics, and cultural significance of meat.

Odyssey Works: What was it like to bleed the boundaries of your real life with that of the performance?

Sasha Wizansky: In August, 2009, I was having a glass of wine with two friends at a home in Brooklyn when a stranger in an overcoat appeared in front of me and handed me a small box full of sage leaves. It was a full week before I thought the Odyssey would begin in San Francisco. He turned and walked away, as quickly as he’d come. My companions refused to acknowledge that anyone had been in the apartment. This was a true surprise, and well-played by my friends. Their silence showed me that this was an experience for me alone and that nobody else would be able to experience as I would. It felt big, special, mysterious, enchanted. My heart was pounding. After that point, I experienced my life in a heightened way. My senses were sharpened. It felt that anything could be a sign, or could be art. Any human interaction could be significant.

OW: This Odyssey entailed a great deal of research into your life. How did it feel to be seen in this intimate way?

SW: Something about the experience of filling out the application questionnaire in very personal terms opened me up for the intimacy of the Odyssey. I willingly engaged with Odyssey Works intimately with my answers to the questions. And Odyssey Works, in turn, continued the conversation before, during, and after the Odyssey. They are still asking me personal questions, and I am still answering them. I don’t think my Odyssey would have been as meaningful if it hadn’t been built upon such a personal dialogue.

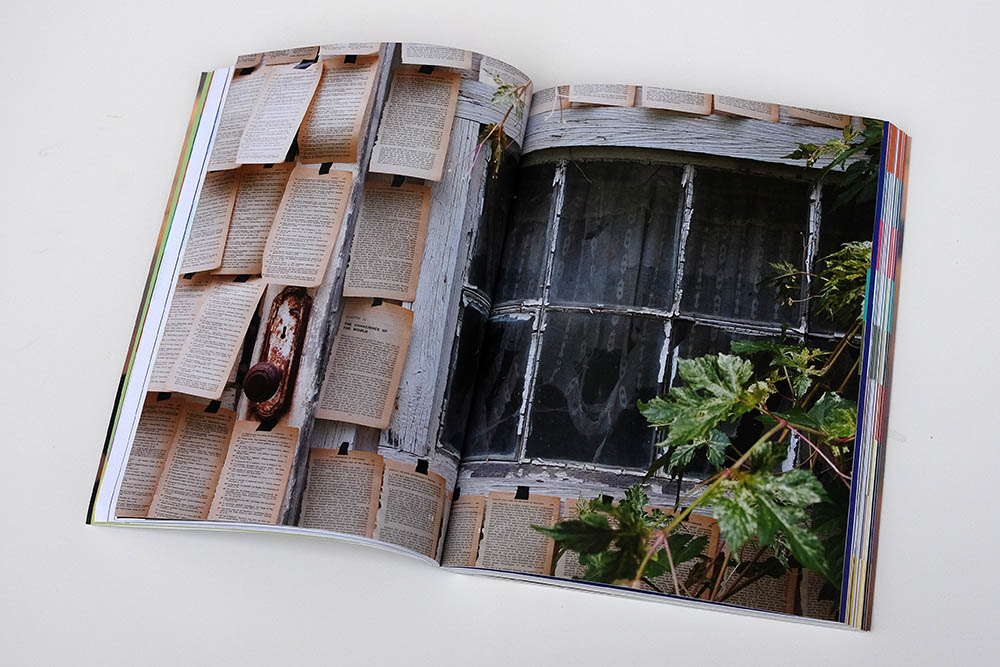

A scene from Sasha Wizansky's Odyssey in 2009.

OW: How was your life changed after your Odyssey? How did the Odyssey affect your life?

SW: This is a bit difficult to pinpoint as the change was subtle and changed over time. I think the Odyssey made me realize how lucky I am. To be gifted an experience of such richness and magnitude is truly remarkable. Very few people have experienced a gift like this. I learned that anything can be art, can be mesmerizing, and can be transformative if properly framed and granted sufficient attention. After the Odyssey I felt cracked open, vulnerable and accessible, open to experience and human connection. I found that telling the story of my Odyssey to friends and acquaintances taught them about the capacity people have to care for one another and inspire one another. The feelings I had weren’t akin to those I feel after seeing a great film or a great play; I had a deeper sense of having experienced something large. As if I’d climbed a mountain, or as if I’d produced the play or a film.

“After the Odyssey I felt cracked open, vulnerable and accessible, open to experience and human connection. ”

OW: Most performances ask that you sit and watch. Odyssey Works requires you to engage fully. How did that requirement change your experience of the performance and did it continue to affect you afterward?

SW: I have never felt so alert or so present as I did on the day of my Odyssey. That day, my car and purse and phone and keys and everything else were taken away from me one possession at a time. At one point I was cast into the city with nothing but an index card and bus fare. There was something profound about having only my body, the clothes on my back, and my perception to guide me. There was nothing to distract me, nothing to hide behind. I was part of the fabric of the city, permeable to everything happening around me, ready to engage with anything, ready to be taken by surprise. During the Odyssey I never felt like an audience member. With nothing to mediate my experience — no cell phone or camera or even pen and paper, I became more engaged with the world and with my senses. I should do this every week. We should all send our friends and family members on small odysseys weekly to inspire them to commune with their unmediated, mindful selves.

A scene from Sasha Wizansky's Odyssey in 2009

OW: What was most meaningful thing for you during your Odyssey?

SW: Throughout the day, there were many astonishingly beautiful moments. When I entered the San Francisco Main Library and saw that it had been subtly transformed into a scene from the ’80s film, “Wings of Desire,” with actors in overcoats on every floor, I am pretty sure I gasped with wonder. But another moment touched me quite deeply. The angel with the feathery wings who had been guiding me greeted me by the tent where I was to sleep that night. She hadn’t spoken all day, but this time she told me aloud that she would be in the field, just on the other side of the fence from my tent, all night, in case I needed her. It was remarkable to feel watched over, not just because she had wings. I suddenly understood that the whole Odyssey experience wasn’t just aesthetic or intellectual — it was also personal. It was about love. There was an angel in a field outside my tent making sure I was ok in the night. It is a fundamental need of humans to feel safe, to feel cared for. Though this might have been a simple element in the narrative of the weekend, it affected me deeply and added warmth to the way I thought about the whole experience.

OW: Based on this experience, what would you say is the benefit of mixing reality and performance?

SW: All around me I see people stuck in cycles of habitual behavior. After walking down the same street every day, we cease to see it. After speaking to the same people every day, we cease to regard them in all their dimensions. After engaging in the same tasks every day, we lose awareness of what we are doing. I think the epidemic of smartphone addiction has exacerbated the human tendency to tune out. When we enter a designated performance space, we similarly approach the experience in our habitual performance-attending mode. But when reality and performance are mixed, our definitions of art are widened and cycles of habit are broken. New pathways of sensory and intellectual experience can be found. I think most people could benefit from questioning their habits of perception. Relationships can be deepened, senses can be heightened, experiences can be made richer. Just answering these questions has provided a well-needed reminder to slow down and pay attention.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.