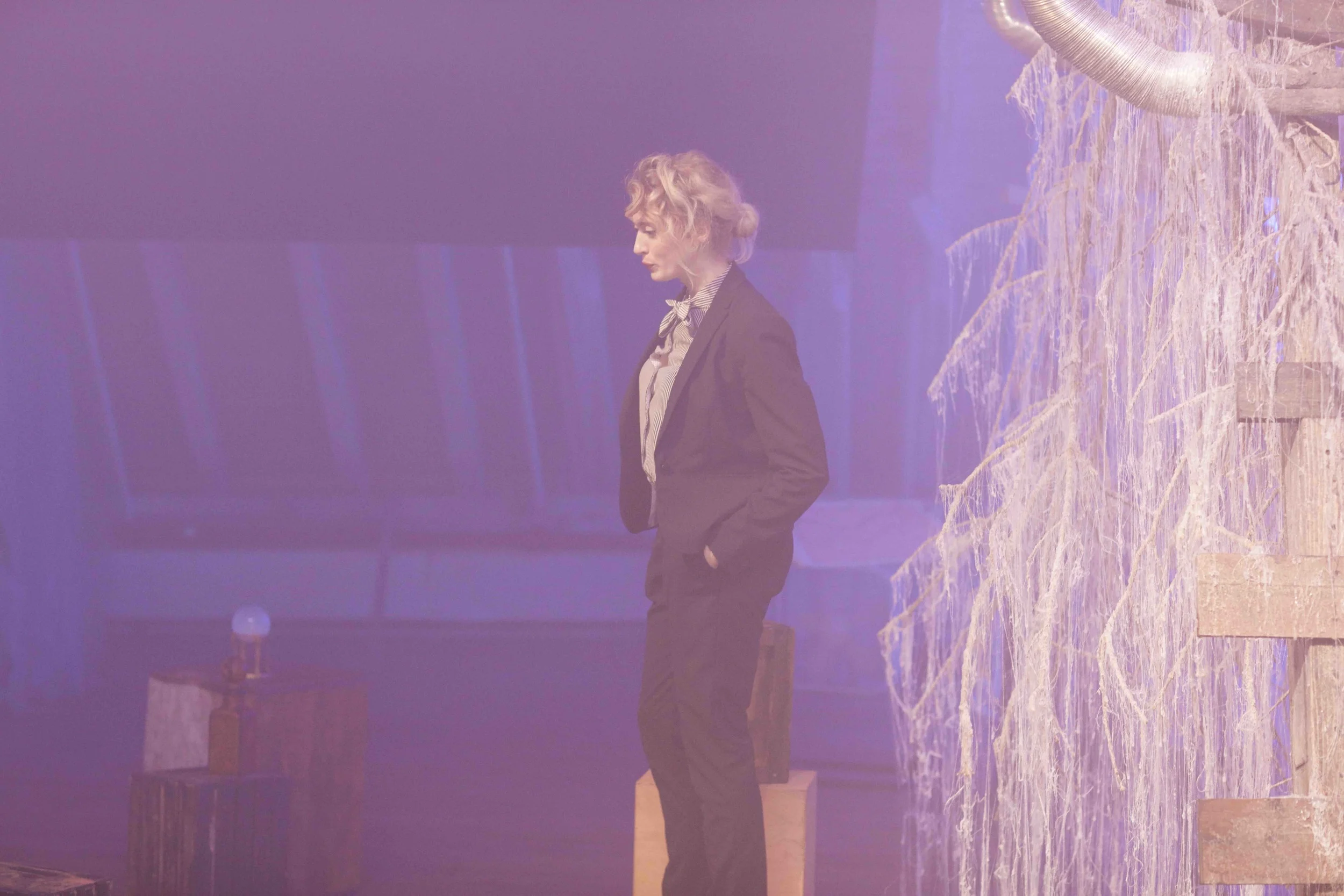

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.

ON THE ART OF CONNECTION

by Ana Freeman

“It is through the possibility of intimacy that the experience of art can be truly transformative.”

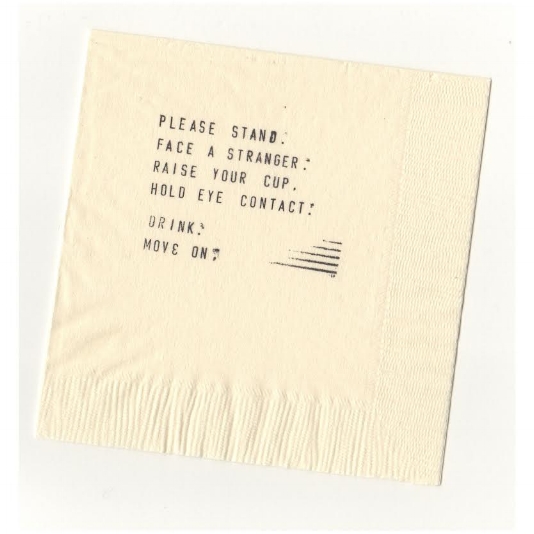

"The desire for connection and the impossibility of it,” said Jim Findlay in our latest interview, “pretty much sum up the whole of human experience, from the criminal to the holy.” Since taking over the editorship of this interview series last January, I’ve spoken with more than a dozen artists. They’ve all had very insightful things to say, but none have stuck with me more than this particular comment. I’m inclined to think it’s true that a desire for connection is at the root of, well, everything. However, I don’t quite agree with Jim that connection is ultimately impossible. I would say that it is rare, but still possible. While we can perhaps never fully know or be known by another person, we can at least feel glimmers of what Marina Keegan called “the opposite of loneliness.” There are many means we have for reaching towards those glimmers. I have recently been working on withholding judgments on the myriad ways people have found to feel whole in the world: to use Jim’s terms, one person’s "criminal" is another person’s "holy."

I moved to New York City about two years ago. It is a cliché to talk about feeling alone in a crowded city, but I have noticed that many people I know do seem to feel disconnected, despite most of us interacting with many people on a daily basis. There are multiple possible explanations: the rise of technologies that enable communicating in impersonal ways; alienation resulting from an urban, capitalist, and competitive environment; rising rates of clinical depression; and the recent inauguration in the United States of a particularly oppressive administration. The extreme political polarization of our country and the violence in our world seem evidence enough that disconnection is not a problem unique to New York. It’s also possible that it has become more popular to talk of a perceived lack of community in recent years because increasing numbers of people have the resources to protect themselves from more pressing practical worries. Nevertheless, we are living in a time where the seeming impossibility of connection is especially potent.

I’ve always believed that art is perhaps more particularly positioned to address the universal human need for connection than most other experiences. But then, where’s the human connection in an abstract painting? There is some message being passed from artist to viewer, of course, but it may be more of an aesthetic or conceptual message than a heartfelt one—more akin to receiving a text than to gazing into someone’s eyes. So though all art is communicative, some of these communications are more intimate than others. It is through the possibility of intimacy that the experience of art can be truly transformative.

Odyssey Works’ first principle is to begin with empathy. For us, this means that we begin the process of creating an Odyssey by extensively researching and interviewing our participant, in order to get to know them as much as possible and gain an understanding of what life in their skin might feel like. It also means that the first intention of the work is that it be designed from the point of view of the participant’s experience, rather than our own. This is the only way for us to make an experience that is truly for and about one person.

I was the production manager for Pilgrimage, the Odyssey we created last November for Ayden LeRoux, our assistant director. Early into the process, I found myself Google-stalking Ayden and constantly thinking about her and how she might react to various pieces of the experience we were planning. For example, when writing couplets that Ayden would find hidden in the New York Picture Library, I adhered not to my own poetic sensibilities, but to what I knew of Ayden’s tastes and history.

The Odyssey centered around Ayden’s knowledge that she carried a gene that put her at high risk for breast cancer. This was not an experience I shared, though I have had medical problems of my own and could relate to the sense of being betrayed by my body. During the planning for the Odyssey, I thought a lot about how it would feel to be in this situation.

When watching a movie or play, there’s a certain process that occurs by which, for the length of the piece, you become the protagonist. The character becomes your avatar for navigating the fictional world, and you share their emotional, intellectual (and sometimes physical, in the case of immersive or VR work) experience. In Pilgrimage, Ayden was the audience member, and I was one of the creators of the work, yet I found myself seeing through her perspective in a similar way, both when planning the Odyssey and during it. Since we spent months creating the piece, this was an experience of prolonged and deep empathy unlike anything else.

Ayden is carried through Brooklyn Bridge Park during her Odyssey. Credit Katy McCarthy.

The fact that Ayden was a real person was also key to this. Imagined characters and situations are often complex and potent, but they can only go so far. Sharing in a character’s experience can be very moving, but I do not believe a relationship with an artwork can compare to a human relationship—unless that artwork itself constitutes a genuine human relationship.

It is for this reason that Odyssey Works strives to create real, rather than make-believe, experiences. Just as an Odyssey is based on a participant’s life, so the Odyssey comes to exist within the real world. Though an Odyssey is composed of scenes, those scenes are not populated by actors, but rather by real people interacting with the participant.

In one scene during Pilgrimage, I gave Ayden a talismanic necklace as she walked across a bridge leading to her final destination, the site of her pilgrimage. As she walked towards me, there was a moment of recognition between us. I recognized her, of course, because I’d been waiting for her, and all my energy was focused on her imminent arrival. But she also recognized me—I was someone she already knew, and she knew I had a role in creating her Odyssey. So I both saw her approaching and saw her realizing that it was me standing there once she got close enough.

I’ve found that acting in front of people I know can be awkward, because they recognize me in spite of the character I’m playing, and this can feel like it threatens the performance. The mutual recognition I felt with Ayden did not threaten the experience, but actually enabled it. Looking back at that moment, I feel that I shared a piece of Ayden’s real journey, not that I played a part in an immersive play created about her journey.

Ayden and I have never sat down and had a long conversation, but I still feel close to her, and protective of her, and like I gave her something that I am proud of giving. I felt privileged to be allowed such deep knowledge of someone. I dove into and explored her experience not because I am her close friend or family member or lover, but simply as in end in itself. In some way it’s the arbitrariness of it that made it so powerful. To partake in someone’s Odyssey is to know that we are all connected, or at least that we can be, if we work at it.

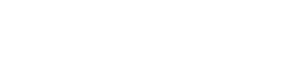

In the spirit of connection, we decided to start this blog in August 2015 to interview artists with similar intentions to our own. Last year, Princeton Architectural Press released a book about our theory and practice called Odyssey Works: Transformative Experiences for an Audience of One, by Abraham Burickson and Ayden LeRoux. If the digitization of communication is one cause of alienation, it also has the power to connect people all over the world, and through the book and this blog we’ve hoped to begin an inclusive conversation. Over the last couple of years, we’ve spoken to conceptual artists, experience designers, performance artists, experimental musicians, game designers, theatre-makers, and culture-creators of all stripes. Via email, phone, and fountain-side conversation, these artists have told us about their ideas, inspirations, and processes. Though we would love to continue the series forever, it is time for us to bring it to a close for the time being. We’ve found a significant sense of solidarity through engaging with like-minded artists, and every one of our interviewees had something new and enlightening to add to the dialogue. With that in mind, I’d like to highlight just a few of the interviews that particularly contributed to our understanding of intimacy in art.

Our interview with Olive Bieringa offered us a stunning view of what making art that stems from empathy can look like. As co-director of the Body Cartography Project with Otto Ramstad, Olive has created several one-on-one dance projects. In her words, this kind of work is a way to “practice being present with another person.” Through movement, artist and audience member give and receive their perspectives and come to a place of mutual understanding. This performance structure facilitates an exciting reciprocal dialogue that disrupts traditional notions of the roles of dancers and audience members.

Kendra Dennard performing with the Body Cartography Project. Credit Sean Smuda.

Christine Jones’ work demonstrates a similar kind of mutuality. Her Theatre for One series consisted of private performances shared between one performer and one audience member. In this model, theatre is not a spectacle or a transaction, but a genuine exchange between two people who share a particular slice of time with one another. She is “an artist who uses intimacy the way a painter uses paint…to make people feel seen, and sometimes…loved.”

Intimacy can go even further when the narrative and symbolic material of the art comes from real life. Tiu de Haan is a beautiful example of this. As a celebrant, she designs experiences for people around major life events, such as deaths and marriages. By using events that are already significant to people as her starting point, she can make experiences that are profoundly meaningful. In detailing her process of working with her participants, she said: “I empathize with their…hopes, and their fears. I build trust, I become their confidant, and I help them to channel their thoughts into a creative container that reflects what is truly important to them.” Her practice is thus founded on authentic listening, which engenders wonder through connectedness.

“The connection found through art is something that is captured rather than invented.”

Emma Sulkowicz also relentlessly pursues truth in her art. Her most famous piece, Mattress Performance, was inspired by sexual trauma that happened in her real life. In her later performances, she has gone even further in working with reality. For example, in Self-Portrait, she answered audience members' questions, but passed along the over-asked ones she no longer wished to answer to a robot version of herself. Reflecting on the performance, she said “I wasn’t changing the way I acted because I was in a gallery. Other people assumed that I would be, because most people really believe in this distinction between art and life, but I’m trying to break down that distinction.” For a more recent piece, The Healing Touch Integral Wellness Center, Emma took on the role of a psychiatrist. My experience of the work was the same as my experience of Emma as a person. In other words, though the work had a specific framework, Emma wasn’t acting. She does not have a medical degree, but she was still her real self in a fictional situation. In a later conversation, she referenced the stereotype that performing artists are performing all the time, even in their real lives. She tries to do the opposite, which is to live her real life even when she’s performing.

It is paradoxical to suggest that the truest intimacy, which is both real and mutual, can be found through art, a medium traditionally thought to be both fictional and unidirectional. I think this paradox rings true because art simply provides a container—a time and space in which we can be with each other—which we don’t often have time to do in the superficial hustle and bustle of our daily lives. The connection found through art is something that is captured rather than invented. As Todd Shalom said to us about his work with Elastic City, “We already have everything that we need, so it’s just a question of reframing.”

...................

ANA FREEMAN was Odyssey Works' 2016-2017 intern, editor of the artists' interview series, and the production manager of Pilgrimage. She also writes for Theatre is Easy and performs with Fooju Dance Collaborative.

JIM FINDLAY ON THE DESIRE FOR CONNECTION AND THE DEXTERITY OF ART

Jim Findlay. Credit Pavol Liska.

JIM FINDLAY works across boundaries as a theatre artist, visual artist, and filmmaker. His recent work includes Vine of the Dead (2015), Dream of the Red Chamber (2014), and Botanica (2012). His video installation Meditation, created in collaboration with Ralph Lemon, was acquired by the Walker Art Center for its permanent collection in 2011. Findlay is a founding member of artists' group Collapsable Giraffe and performance space The Collapsable Hole. His work has been seen at BAM, Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, Arena Stage, A.R.T., and over 50 cities worldwide, including Berlin, Istanbul, London, Moscow, and Paris.

“We’re all here. Alone and together.

”

Odyssey Works: What are you trying to achieve with your art?

Jim Findlay: I’m just trying to achieve some art with my art. I’m pretty satisfied when I feel like I’ve done that.

Thinking of the work I make in terms of other senses of "achievement" feels like trying to change a tire with a poem—which sounds like a good way to make art, even though it’s a stupid way to change a tire.

I’m basically down with the idea that what makes art unique is its uselessness. If its use is immediately apparent, then it’s hard for it to be interesting. You have to look at a wrench for a really long time to see the poetry in it, because it’s hard to stop seeing the wrench. But if you can make something that's interesting and also quite apparently useless, then I feel like that’s something that fires up the curiosity neurons.

Vine of the Dead. Credit Paula Court.

OW: Why integrate multiple disciplines? What is the best way to approach this?

JF: Approach it by just diving in and using it, whatever it is. Use it wrong, use it stupidly, use it as incorrectly as possible. Don’t fall into the trap of having to understand it before you try it. It’s not about mastering something, it’s about bending it to its own special state of uselessness.

Humans are omnivores, utter generalists, pansexual, and inherently curious. We are probably one of the least specialized species on the planet. Why would we be wildly dextrous and flexible in every other aspect of our existence, but not in our art-making?

I find words and speech much more foreign than the physics of electrons and photons or the elaborate syntax of contemporary digital language. We’re living in a time of widespread visual and sonic literacy. Lay people are incredibly sophisticated about the language of the jump cut and the slow fade. Using multiple disciplines feels quite organic. I don’t think about it much. I just do it.

“I think the desire for connection and the impossibility of it pretty much sum up the whole of human experience, from the criminal to the holy.”

OW: Speaking of combining forms, your work frequently combines recorded and live performance. What is the reason behind this?

JF: It’s so much more mixed up than anyone can imagine! A lot of the media work I do is predicated on live performers using the technological medium, sometimes swimming in it. Integration of media for me means that it’s integrated into the bodies and actions of the performers. For example, in Dream of the Red Chamber, there is constant video presence in a truly epic way. But a deceptively large portion of that video is live. The technology’s main function in the world of the piece isn’t its content. Rather, its most essential function is that it occupies the performers' actions. I enjoy watching people struggle to do something difficult; using technology in performance in a rigorous way is difficult, especially when it’s largely controlled by the performers themselves.

OW: A lot of your work has an epic quality. Yet it has also been described as "intimate." This seems counterintuitive, as we usually associate intimacy in art with a more minimalist aesthetic. How can a vast scope be intimate?

JF: Creating dichotomies, tensions, and seemingly incongruous feelings is something that is very conscious in my work. And I think that we never feel more intimate to ourselves than when we feel ourselves small inside the vastness of life and the universe. There’s something about loneliness that’s not on the surface often, but that nonetheless is a strong undercurrent to everything I am. I think the desire for connection and the impossibility of it pretty much sum up the whole of human experience, from the criminal to the holy.

Dream of the Red Chamber. Credit Paula Court.

When I make worlds—and to me, making a piece is like making a world because it has its own set of functions and rules and features—I always want my worlds to have their own integrity. They don’t have to be realistic, or operate on the same principles as our experience, but they have to make sense on their own terms. I think that epic feeling in my work may come from my desire for a piece to have its own special autonomous feeling. I feel like the intimacy element is even more essential, and that comes from my real desire to just be there with everyone. The performers and I are not going to pretend to be other people, at least not in ways that aren’t utterly transparent, and you don’t have to pretend you’re not here either. We’re all here. Alone and together.

OW: In your performance Dream of the Red Chamber, the audience is encouraged to experience the work while drifting in and out of sleep. How does this enhance the experience? What is the connection between dreams and art?

JF: The piece makes a simple proposition: What happens when we disrupt the usual transaction between the audience and the performer? What if the audience doesn’t have to pay attention and the performer is released from their duty to entertain? Everything in the piece is in service of this proposition in some way.

“Did I make that? Did she make that? Did it happen? Does it matter? ”

I also admit that I have a lot of firsthand experience of sleeping in theaters. And I always find the haze of liminal states between being asleep and awake very pleasant. So when formulating the piece, I had a pretty good idea of the experience I was proposing to the audience.

The other aspect of this that became important for me on an aesthetic development level was that it forced me to relinquish control of the experience. A friend at the show fell asleep, and in her dream the show continued, but there was a large curtain near where she was sleeping. The performers made a big show of opening this curtain, and behind it was this very large beloved painting she had done 20 years ago that she thought had been lost forever. It was still lost in real life, but was returned in the dream. She woke up at the show crying because we had returned her painting to her, and it took her five to ten minutes to sort out what the reality was and what had been in her dream. Did I make that? Did she make that? Did it happen? Does it matter? That’s a pretty good demonstration of the connection between dreams and art, I think.

OW: Who are your influences?

JF: Captain Beefheart, La Monte Young, Elizabeth LeCompte, Reza Abdoh, Derek Jarman, Mark Twain, Kathy Acker, Werner Schroeter, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Ralph Lemon, Amy Huggans, Iver Findlay, Radiohole.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.

SPRINGBOARD COLLECTIVE ON FUN AND TOGETHERNESS

Sarah Dahlinger, Danny Crump, Micah Snyder, and Stephanie Wadman of Springboard Collective. Credit Danny Crump.

Springboard Collective produces collaborative, site-specific, interactive, and immersive sculptural environments. Utilizing experimental and imaginative approaches to everyday materials, their installations focus on transforming the physical and psychological aspects of fun through socially engaged events. Their works include Good Humor (an ice cream-making extravaganza), Total Limbo (a fanciful fort), and Soft Surplus and Soft Surplus+ (inclusive playlands). Springboard Collective is directed by Danny Crump, Micah Snyder, and Sarah Dahlinger, and is also comprised of Stephanie Wadman and Barry O’Keefe. Contributing artists include Todd Irwin, Siavash Tohidi, Matt Hannon, Juniper Nova, and Ryan Davis.

“It’s not about me or you, it’s about us. ”

Odyssey Works: What led you to your current approach to art-making? How did you start breaking traditional molds?

Springboard Collective: Springboard Collective started in graduate school at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. Danny had done a residency at Flux Factory in 2014, and got inspired by all the collaborative work happening there; it dawned on him that you could get a lot more stuff done faster and be more improvisational with other people. So he proposed starting a kind of band where we would make collaborative art shows. We were all a bit disillusioned with the isolation of the grad school grind, and we wanted to experiment without the pressure of individual authorship. We wanted to let ourselves be really playful with materials and with ideas without overthinking them beforehand. So we began making these ambitious spectacles with a little bit of painting, a little bit of sculpture, and some kind of social interstice all coming together.

Good Humor, 2015. Credit Danny Crump.

OW: Tell us about your process.

SC: We all bring different skill sets to the table and we are continually pushing and pulling and learning from one another. There are specific things that one of us will get obsessed with doing, like individual videos, but part of the process of working collaboratively is to surrender ownership, and to share credit and responsibility. It’s not about me or you, it’s about us. We tend to work on tight timelines, so it’s a really intensive work period. We might plan a project for three weeks. We usually have a big brainstorm on a big piece of paper, and we just write down every idea that anybody comes up with. And then we figure out how we’re going to fit it all together. We mock up the bigger structural elements, sketching things out in real space. We often have only a few days to build the whole entire thing. So there’s a lot of thinking, then a lot of work, and little sleep. And that’s liberating because it's gestural and fast and we don’t have to nitpick all the little details. We follow the impulse, follow the imagery, follow the materials, and just let those lead us wherever they go.

“We aim to be impish.”

OW: “Fun” is a word you frequently use to describe your work. What does this mean to you?

SC: We aim to be impish. Our pieces give people permission to act a little crazy and be a little weird, which ends up facilitating fun and togetherness. We are creating a new sort of environment that’s a land of escape from actual reality, and the levity of it is refreshing. The things we reference, like ice cream, bouncy castles, and mazes, are all very playful and childlike. One reason we have for working together is wanting get back to a childlike sense of making, and being really open and fearless. It helps people get out of the day-to-day. A lot of times when you go to shows and museums, you’re still contained in yourself, you’re still reserved. But if you have box of costumes, and you put on a wig, and you get thrown into this tiny area where there are 20 people jumping and everything’s going crazy, it facilitates this experience of breaking free and letting loose for a minute. Another thing about a lot of our work is that the pace of people moving through the space is totally different from a typical art-viewing experience. When you walk into an art space, you typically slow down, but all of our shows have this buzz to them. People are really moving around, getting comfortable, getting immersed.

Good Humor, 2015. Credit Matt Hannon

OW: Can you speak more to immersivity and interactivity? What do those words mean to you and why are those elements that you want to include in your work?

SC: The installation format is nice, because you’re not dealing with one material or one medium. Everything all has to work together. In all of our pieces, we’re making something that is interactive because we want to give ownership to the people that are coming to become a part of it. We set up this template for them to inject their own creativity into. They’re churning the ice cream that they’re going to taste, they’re making the sculptures that they’re going to take home. It’s an extension of the process of making to the audience. And it’s a really awesome kind of leveling of different hierarchies of people. Our environments are something that you come and interact freely with. There are no rules. And immersion is necessary because it’s a break from reality. We all need to have moments of escape from whatever pressures we experience, so we provide a space that you can step into and, at least momentarily, be liberated. It’s an offering of a space to be together and work together, and that’s a genuine gesture on our part. If you look at the headlines recently, our type of fun, cheeky event might be just the type of thing that we need right now. In our work, nothing’s too serious.

“We’ve learned that you can make art out of anything if you just put enough effort into it and belief behind it.”

OW: In interactive environments, where do you locate the art?

SC: All of it is the art. And we don’t keep track of any individual’s physical input into a piece. That’s the beauty of it, that it all sort of melts together.

OW: Why create experiences?

SC: We do have relics from our pieces: the objects produced as part of the event. Those have spread out—some people have taken them home—and they do carry a little bit of the energy from the show. But it’s hard to describe all the stuff that happened in any one of our pieces. You really had to be there. We’ve learned that you can make art out of anything if you just put enough effort into it and belief behind it. We start from kind of silly ideas, but then take them to a level where there are much more interesting questions being opened. And the overall experience of the event is where that magic happens.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.

Stranger Kindness, a review

How does language make meaning? When we witness a narrative unfolding – especially one that is structured and performed as fiction and thus as a composition to be comprehended – how tightly do the words need to relate to the structure of the story to be relevant? We see it all the time – the words we speak careening from direct communication to a masking of subtext to comfort-inducing digressions. Language folds and overlays and flees meaning and yet somehow we are able to assemble stories from its incredible choreography. Such complexity! And still we find time to revel, on occasion, in the pleasures of language.

Stranger Kindness, a violently disassembled adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, features Marlon Brando’s recorded voice (from the movie) in the role of Stanley Kowalski. It’s a movie I’ve seen countless times – a hot and raw film indulgent with the sweet pleasures of language. The story is a classic tale of a fallen woman, returned to New Orleans after losing everything and leaving her hometown in shame. It’s a story about masculinity and femininity, and the tortuously structured choreography of a woman’s role in a world dominated by men. It is tragic and elegant, and one of my favorite movies. I recommend seeing it.

Then, I recommend going to Stranger Kindness. None of the rest of the lines in the play spoken by the actors are from the actual play. Rather, they speak lines from other plays and other texts. The cast learned the original lines first, along with the original intonation – the accents and the mid-century exuberances – and matched it to the blocking. Then the directors (Lola B. Pierson and Stephen Nunns) replaced the lines with lines from other texts that were relevant but egregiously different. Stella and Blanche and Mitch argue and cry out and insist with complete conviction, but with the wrong words. Sometimes the words are relevant – when Blanche is disappointed by someone’s reaction, she says, for instance, "One day you'll be blind like me and you'll be sitting there a speck in the void," words that get at the emotional valence of the moment but fudge the informational content. Or Blanche’s suitor, Mitch – the man who just might be her last hope for a decent life – while trying to force an unwanted kiss will pronounce feminist critiques, declaring “Woman’s degradation is in man's idea of his sexual rights.”

Sometimes the words themselves are a commentary on the actions of the character – the critic’s voice moving through the scene. Sometimes they are a displacement of meaning. Sometimes they are just funny. The whole experience is uncanny, difficult, and exhilarating. The actors’ exaggerated body language and intonations loudly structure the meanings of their utterances, so that we can pretty much read the intent, but the language they use both undermines and enlightens the scene. We are never certain if the text is text or subtext or commentary or just confusingly relevant; because of this, I spent the entire play as a birdwatcher in a language sanctuary, observing the behaviors of words, seeing how they accrue to meaning and leave it, and occasionally stepping aside from the confusion of it all to wonder at the sublime mechanics of this system we take for granted.

In a nod to the great Polish director Jerszy Grotowsky, the audience is seated above the stage, looking down upon the action. I was not sure why Grotowsky did this, and if there was some meaning in the Acme Corporation’s version it was lost on me as well. There were also a lot of televisions with cut up scenes from the movie occasionally interrupting the action. For me these were helpful as a grounding device, but I suspect there was something deeper intended with them that was lost on me.

The play is also, of course, about mental illness – such a taboo and important subject. I often feel that art is all about mental illness in some way or another – at least the art I enjoy – as it tends to break with standard patternings for “normal” life, working both as a critique of normalcy and a remedy for it. We track mental illness primarily through language. Most markers for madness are perceived through language and, more specifically, through language that deviates from expectation. This production is all about that deviation, so it is appropriate that Blanche only returns to the original text at the end, when she is being carted off by the men in white jackets. It is the title line – her go-to line: that she has “always depended upon the kindness of strangers.” The final note of Blanche’s story is a desperate grasping for a normalcy that will everafter evade her, and one that this adaptation refuses to strive for at all.

The Acme Corporation’s Stranger Kindness is directed by Lola B. Pierson and Stephen Nunns, and is playing at St. Mark’s Church at 1900 St. Paul Street in Baltimore through Dec 17, 2016.

review by Abraham Burickson

cover image by Tania Karpenkina

After Trump: Why Art Must Go On

I woke up this morning uncertain how I would be able to attend the book release of the book I co-wrote with Ayden LeRoux. It seemed frivolous, like painting the house while Vesuvius is erupting. Add to that the performance I’m producing with the Odyssey Works team this weekend — a thirty-six hour long experience for an audience of one person — an experience aimed at the subtle narratives of that person’s existence, at the interplay between meaning and states of perception, at the potency of empathy. How to do such a thing when facing the reality that a man who has admitted to sexual assault, reveled in racism, and celebrated his megalomaniacal narcissism is now poised to be our commander-in-chief?

CHLOË BASS ON INTIMACY AND LIVING BETTER TOGETHER

Credit Chloë Bass.

Chloë Bass is a conceptual artist working in the co-creation of performance, situation, publication, and installation. She's recently returned to Brooklyn after a summer making work in such places as Greensboro, New Orleans, St. Louis, and rural Nebraska. Chloë is a visiting assistant professor in social practice and sculpture at Queens College, CUNY. She is sometimes a collaborator, sometimes published on Hyperallergic, and adamantly and always a New Yorker. You can learn more about her at chloebass.com.

“The world is something that we make together. ”

Odyssey Works: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

Chloë Bass: The world is something that we make together. (Joseph Beuys even called the world a collaborative artwork.) There are a million tiny gestures that go into the fabrication, presentation, and maintenance of art, not to mention society. We are not always equal players; equality may be rare, or even impossible. I have no problem being an authorial voice, a game-maker, an editor, a social designer, or a leader. But I think what we forget is that these positions, except in extreme fascist cases, actually require the participation of others. My work is a series of experiences for people. It exists in the moments where it’s happening, in the echoes my participants take with them, and in the ways they and I find to share some element of what occurred with those not present.

OW: Your work often relies on relationships or interactions between two people. How does intimacy play a role in what you create?

CB: I’m actually scaling up. I’m going gradually, so I think it’s pretty hard to tell at the moment. From 2011 to 2013 I worked at the scale of the self, and produced The Bureau of Self-Recognition, a conceptual performance and installation project designed to track the process of self-recognition and its myriad outcomes. Since the beginning of 2015, I’ve been working on The Book of Everyday Instruction, which explores on-on-one social interaction. I have some exciting ideas for the next phase after that. I don’t want to say too much at the moment, but I’m looking to work with family-sized groups, and I want to make a film.

I’m preparing myself to tackle groups of people the size of entire cities, eventually. The artist Elisabeth Smolarz came to visit me in my studio a few months ago, and she joked that the ultimate manifestation of my practice would be to become president so I could do a project with the entire country. I'm learning alongside my work. I am genuinely teaching myself about the world through these artistic actions, interventions, and experiences.

I'm not necessarily an extroverted person. I think I really thrive in the depth of the magical space that can be created between two people—until one of them has to get up and go to the bathroom, and the moment breaks, and they’re back to being their regular, awkward selves in the world. I like the connection and the breakage, to be honest. I think there’s a lot of power and material in both.

It's amazing we don't have more fights, participatory performative workshop, 2016. Credit Manuel Molina Martagon and The Museum of Modern Art.

But I want the breakage in my practice to be a conscious choice. Can we maintain the intimacy of the pair at the scale of a city? What remains, and what is lost? How can I hold people, and when is it informative to let go?

I wonder often about incorrect intimacy, and the special space it creates. I was in Cleveland for two months in 2015 spending time with strangers, joining them in their daily lives. A large part of this project turned out to be getting in the car with strangers, something we’re told not to do from the time we’re very young. There was something about beginning with an “incorrect” gesture that made my participants and I responsible to one another. Changing the usual circumstances of how and where we meet people brought us into a different kind of social and aesthetic world. Doing things wrong can hold high imaginative potential.

Recently, I was in St. Louis, where I talked to people about safety and safe places. For me, taking a stranger to a safe place and having a conversation about safety is really odd and anxiety-provoking. It’s essential to make sure that the best parts of that oddness are preserved and turned into something productive. At the same time, I have to work hard to make myself extra comfortable for the person who’s allowing for this vulnerable interaction to happen. Balancing these kinds of dynamics is a huge part of my craft.

OW: How do you understand immersivity and interactivity? How do they work and why do you use them?

CB: Well, those are the materials of life! Every experience that I have in my daily life is, to some extent, unavoidable. I might willingly choose to enter a situation, but what happens once I’ve entered it is just the product of being there.

That said, people can occupy the same space and have entirely different lived experiences. I feel a little bit suspicious about immersivity right now. What does it really mean to be immersed in anything other than your own subjectivity? How can we extend the bounds of the personal in order to improve our treatment of others? I am not speaking of empathy, which does the work of making us all affectively the same, but of a certain kind of non-understanding that teaches us we need to do better.

“Form is a kind of stitching, a way of putting a temporary experience into a more permanent shell. ”

OW: How does the social component of your work relate to the material forms you create? How do you categorize your work?

There was a time when I used to edit my artist's statement to rename myself as the type of artist I had most recently been called by others. If a review came out and said I was a performance artist, then I would call myself that. I did this not out of inherent resistance to categorization, but because I felt really new to making my own work, and was just as willing to trust others to name it as I was to trust myself.

Now I teach social practice in the art department at Queens College, and there are so many people who call me a social practice artist. From an academic and art historical perspective, I have to say that I’m not so sure they’re right. I think social practice is best described as a series of tactics that’s been culled from many fields: anthropology, sociology, psychology, community organizing, trauma studies, journalism, and, yes, art. I can only classify some of my own projects in this category. But I am an artist who works with people, that much is certain.

My current statement says that I’m a conceptual artist working in a variety of forms: situation, installation, publication. Naming myself a conceptual artist has made it ok to be making work that exists in service of a series of related ideas, rather than a series of related material practices. Form is a kind of stitching, a way of putting a temporary experience into a more permanent shell. However, the shell is really just a reminder that something has happened.

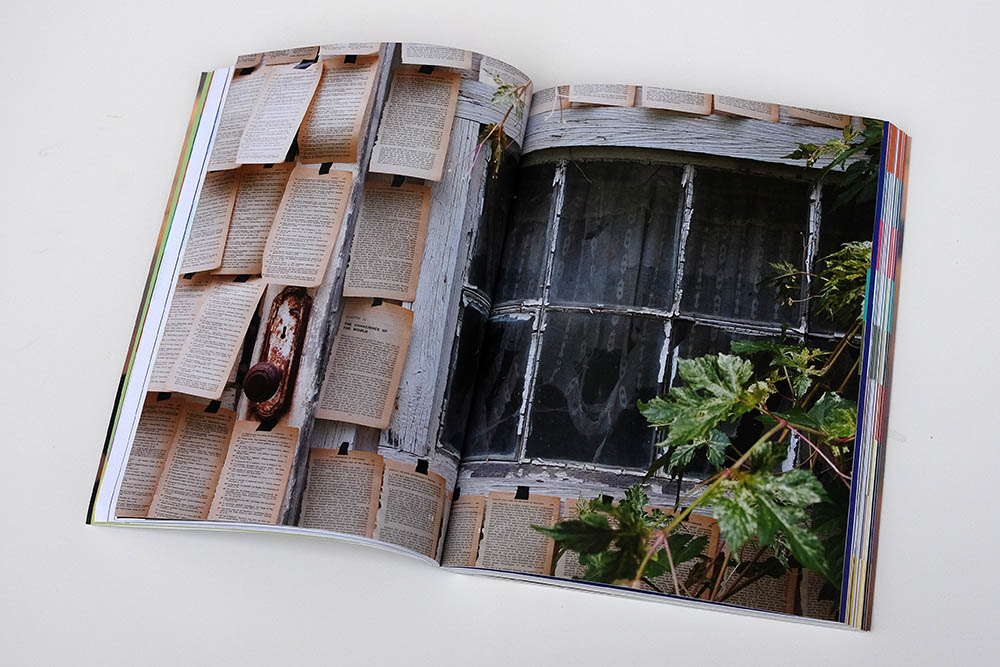

Hand-stamped cocktail napkin from Linger Longer Toast, a participatory public performance that took place in 2014. Credit Chloë Bass.

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience of art that transformed you?

CB: When I was about eight, the Guggenheim had a retrospective of Rebecca Horn’s work on view. In the museum’s oculus, Horn had hung a grand piano, which “exploded” a set number of times per hour: keys and hammers appeared to fly out of the instrument, accompanied by a dramatic sound. I loved how scary it was, how funny it was, and how we couldn’t avoid it. I don’t know that Horn’s work is a visual influence on what I do, but I’ll never forget that moment, or how it’s continued to shape my social and emotional responses to artworks.

I am also hugely influenced by Adrian Piper, Andrea Fraser, Claudia Rankine, Maggie Nelson, and Doug Ashford. And I’m a habitual eavesdropper and casual voyeur; I don’t intend to stop being inspired by these arguably creepy practices.

OW: What are you trying to do with your work?

My goal is both incredibly simple and insanely grandiose: I want us to live better together. Every piece of work that I make is in service of this aspiration. The experiences I make are triggers for a feeling. It’s on you to figure out what to do with that feeling, and how to use it in your relationships to others. The objects I make are souvenirs, tagged with memories that you might rediscover later. The words I offer are guidelines. But making the world? That’s yours.

...................

Interview by Ayden LeRoux and Ana Freeman.

KATY RUBIN ON REALITY AND TRANSFORMATIVE ACTION

Katy Rubin. Credit Will O'Hare.

KATY RUBIN, Executive Director of Theatre of the Oppressed New York, is a Theatre of the Oppressed facilitator, actor, and circus artist. She has facilitated and directed forum theatre workshops and performances in partnership with various communities, including LGBT homeless teens, people living with HIV/AIDS, recent immigrants, and court-involved youth and adults. Katy studied with Theatre of the Oppressed inventor Augusto Boal at the Center for Theatre of the Oppressed in Rio de Janeiro, as well as with Jana Sanskriti in India, Mind the Gap in Yorkshire, and Cardboard Citizens in London. She has trained facilitators around the U.S. and Europe and in Nicaragua.

“Everyone is a spect-actor.”

Odyssey Works: What is the mission of Theatre of the Oppressed NYC and how do you achieve it?

Katy Rubin: Theatre of the Oppressed NYC partners with communities facing discrimination to inspire transformative action through theatre, that’s our mission. We pursue that, I would say, rather than achieve it, by partnering with social service organizations, city agencies, and sometimes neighborhood groups to start ongoing popular theatre troupes—popular theatre meaning theatre of and by people, rather than necessarily professional artists. And those troupes build plays based on their shared experience of oppression and the questions that they want to ask their larger community about urgent human rights, civil rights, and community rights challenges they're facing. Each play focuses on one specific problem. They tour performances that they’ve built together to theatres, to other communities, to shelters, to clinics, to peers and strangers, to engage in creative problem solving together onstage. All our plays involve a forum, where the audience is invited onstage to try out alternatives to the problem, and then we have a critical analysis of those alternatives. Sometimes we involve policymakers in that forum, to try to take those ideas from the audience and the actors and turn them into concrete institutional change.

OW: In forum theatre, there are no spectators, only “spect-actors,” as you call them. So everyone in the room is in some way responsible for creating the experience. If audience members choose not to get up on stage, how do they contribute to what goes on? And in a theatrical event that is created collaboratively, where is the artwork itself located?

KR: We don’t believe that change is made by forcing anyone into anything, so we don’t force our actors to participate, and we don’t force our audience members to participate. That said, we don’t let the whole audience sit there silently; at least some people in the audience have to take action.

There are a lot of ways to engage. First of all, people engage by choosing to come, and it’s free. That’s important, because it relates to how much you can participate. If you had to participate by paying $150, maybe you don’t want to participate further, because you gave all your resources already. Second of all, we ask the audience members to raise their hands and identify if they’ve been in a similar situation or can see how the problem onstage relates to their life, so they engage by identifying that they have some relationship to the problem. Thirdly, they engage by speaking about what they see, what they saw people try, why it might or might not work, and what changes would need to be made for it to be implemented. And then, of course, they engage by getting up and trying something, which is the riskiest form of engagement. But we’ll never have an event where we allow people not to take that risk. The whole audience is on the spot to see who from their group is going to step up. If nobody steps up, then we say, “Essentially you’re saying you want these problems to continue they way they are.” They have a choice, but they saw how oppressive the situation was.

We want to move people towards choosing to be in solidarity with their neighbors, which means that we have to allow for different levels of engagement. So just as with any kind of community action, we need people to participate in all different kinds of ways.

Audience members voting on a policy proposal at the 2015 Legislative Theatre Festival. Credit Will O'Hare.

If a play solves a problem for you, it’s not very participatory, because you don’t have to put your brain into addressing a problem. If a play leaves a problem open for you, then it's more participatory, because you have to think about what should happen to solve it. Are you going to do something about it, or are you going to wait and be complicit in not doing something about it? There are varying levels of participation, but it’s about not only what you do in the theatre, but also what the play demands of you.

In terms of where the art lies in participatory theatre, I believe that everyone is an artist, so I can’t pinpoint one place there is art and one place there isn’t art. And in our work at Theatre of the Oppressed NYC, the person onstage could have just joined that troupe that day. There’s no hierarchy of artists.

Everyone is a spect-actor. The actors are spect-actors, because they’re watching their lives and then they’re taking action. The audience members are spect-actors, because they’re watching the play, watching their lives as they relate to the play, and then taking action. Everyone is watching, observing, thinking, analyzing, and doing. Acting is taking action, in our definition, so our definition of art is the use of an aesthetic expression to evoke feelings that move people to action. And anyone can do that—by painting a picture, by making a play, by making music, by speaking beautifully, by writing poetry. So it’s available to the audience to do that too.

OW: Forum theatre keeps the spect-actors at a critical distance, allowing them to think about what they're seeing and come up with ideas to try out. To the extent that this distance also limits the audience’s ability to relate to the story, how do you prevent that from hindering their motivation to become involved in making change? How do you balance the respective powers of thought and empathy as jumping off points for fighting oppression?

KR: We believe in feelings that incite people to action. We don’t believe in feelings that just allow people a release so they can go back to their lives and not feel like they need to take action. Augusto Boal, who invented Theatre of the Oppressed, wrote about being anti-cathartic. In other words, we don’t want our audience to say “I saw a tragedy and now I feel cleansed.” We want them to say “I saw a tragedy and now I feel bothered, and now I’ll go do something about it.” Emotions are great for inspiring people to take action, and that's why we present plays and not just lectures, because plays do evoke emotions, and we want people to feel moved, upset, amused, all of those things.

OW: Do you evaluate the quality of your performances entirely by their effects, or is there some measure of craft, of aesthetics, of strength of narrative through which you decide you've created something of high quality?

KR: We do try to evaluate the narrative, the craft, the funniness, the moving-ness. We’re most concerned with if the play holds together as one story. Does it have a beginning, middle, and end? Is the problem, in all its complexity, clear? Do we understand the consequences when people can’t quite get what they need, in terms of how this affects their lives and why it’s important? Do we see the other people in the ecosystem of the story? Are there allies? Are there aesthetic elements that support the narrative? Do the props support the story, does the music support the story? As in all theatre, the most important aspect of the production is that it supports the narrative, so in terms of what specific aesthetic qualities we aim for, it depends on the specific story.

That said, we do use the distancing effect you mentioned, so we allow the audience to see the lights and the costume changes, and we use cardboard props. We want to take the magic of the theatre away so that people will really think. As Boal used to say, “We want reality, not realism.” Sometimes that means we have an aesthetic element that’s not “realistic,” but actually heightens the reality, and we want that reality to hit people. And if people are alienated from their feelings by the fact that the play doesn’t look like a beautiful Broadway show, then we also want them to understand that not all art looks like a beautiful Broadway show. We want them to get over that, so that they can be present. We want to teach people that what we do is also an expression of art. It’s about access, too. Art can be what you make in half an hour, because you don’t have access to a theatre and a set and a costume designer, and we want to make our audiences aware of that.

Actors in Homestead Instead: Reclaiming the Dream, a 2016 forum play. Credit Devyn Mañibo.

OW: Tell us more about the relationship between the world of a forum play and the world outside. Actors devise a play from real-life problems, but how do the solutions found in a forum then get brought back to real life?

KR: That happens through legislative theatre, a type of forum theatre where we involve policymakers in the process who bring the ideas we have back to the institutions they work in. We also do follow up to every show through email and social media to encourage people to come to protests and other actions. And we try to get them to come to more shows by keeping all of them free and accessible. But I would say that we haven’t nailed all that down yet.

We’re asking people to think about a problem and take action about it as if it’s their own, but the rest of the world is supporting them in not taking action with their neighbors. The news just sensationalizes things and creates fear but also distance, and commercials just tell us how we can lose ourselves in buying new objects. It’s really hard to keep people motivated outside of the short time that they spend with us. We do our best, but we’re just a small part of the movement that’s fighting for people to “stay woke,” as they say, in a culture that’s trying to get people to stay asleep. I don’t think that we can do it by ourselves.

With our former actors, some say that now they call their council members and their state senators and their senators. They take action in ways they didn’t know they could before. They feel connected to some of the politicians who come to our annual Legislative Theatre Festival. Some start getting more involved in the arts. Sometimes they get involved in other socially engaged arts organizations after they work with us, and that’s awesome. There are so many similar organizations out there working in all kinds of mediums.

“To truly move people is to move people to go out and take action in the world. ”

OW: Theatre of the Oppressed NYC is an unusual theatre company in that you explicitly and directly aim for sociopolitical change. It is more common for theatre to attempt to facilitate some kind of catharsis or transcendence. What is your view of the interplay between these different modes of artistic transformation?

KR: People can have personal transformations any time they want, but what we’re really looking for is personal transformation from you as a watcher into you as a doer. We want to change hearts and minds as much as anyone, but that’s just the beginning. To truly move people is to move people to go out and take action in the world. We want people to rehearse taking action in the theatre, and understand how individual action works, how collective action works, how sociopolitical action works, and why you need all three of them. We want to actually generate some potential solutions in the theatre. That doesn’t mean that people won’t have to change their behaviors outside the theatre—they will. We can’t solve things completely, but we want to use the space we have as a lab to explore what we will have to do once we leave. And we want to build a community out of the audience that will decide to take action together outside the theatre.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.

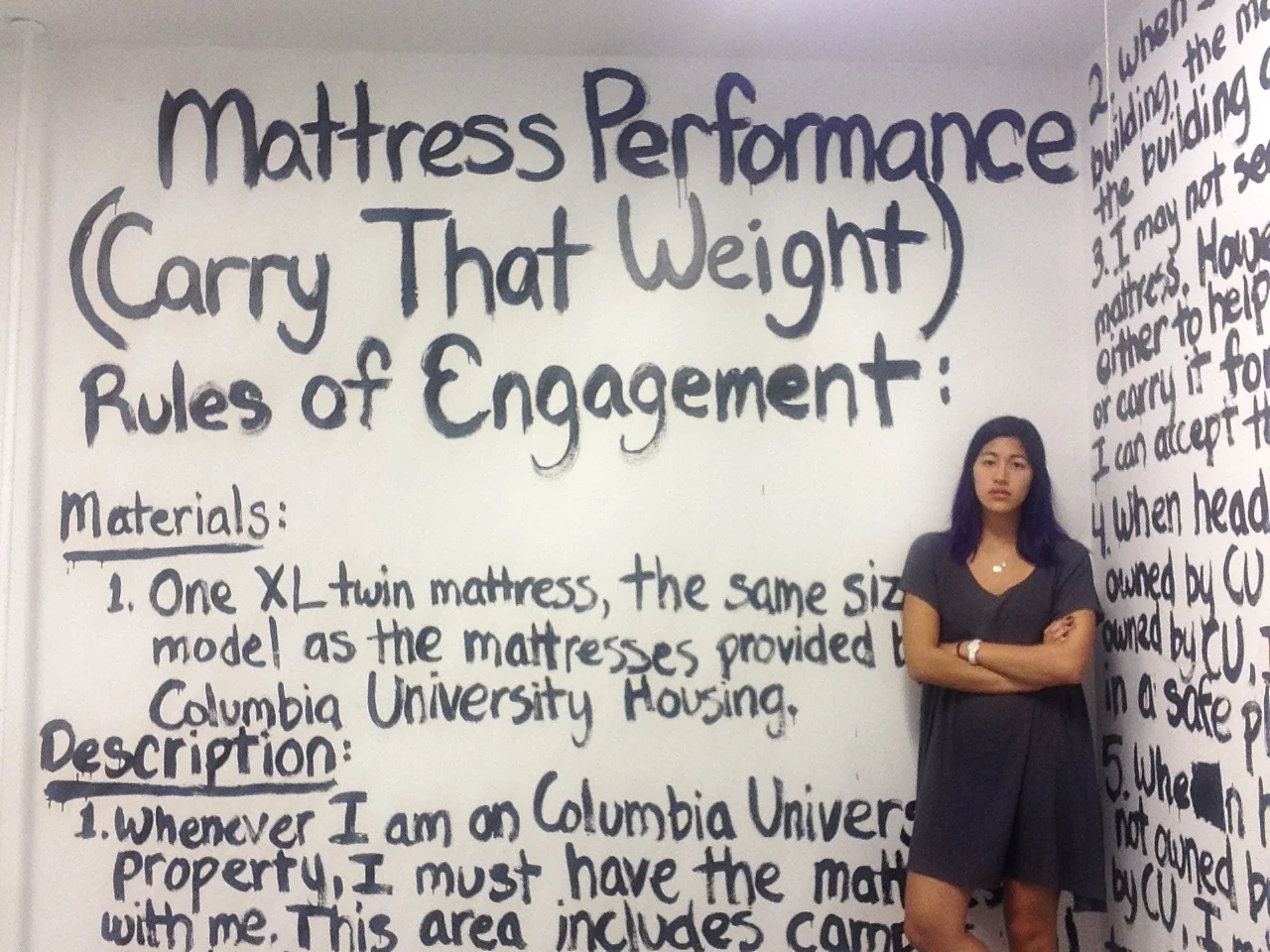

EMMA SULKOWICZ ON THE PERFORMANCE OF LIFE AND THE MAGIC OF PARTICIPATION

Emma Sulkowicz. Credit Joshua Boggs.

EMMA SULKOWICZ lives and makes art in her hometown, New York City. She is best known for her senior thesis at Columbia University, Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight), an endurance performance artwork in which she carried a dorm mattress everywhere she went on campus for as long as she attended the same school as the student who assaulted her. Her more recent works include Ceci N'est Pas Un Viol, an Internet-based participatory artwork, and Self-Portrait (Performance With Object), in which she made herself available to answer questions from viewers, but referred questions she was not willing to answer to Emmatron, her life-sized robotic double.

Odyssey Works: A lot of the work you do is long durational, and that’s unusual in our age of fast-paced media and fast-paced lives. However, you also heavily utilize technology. What inspires you to work in these differing forms?

Emma Sulkowicz: Well, how boring would it have been if I had carried the mattress for only one day? For that piece, it seemed like long durational performance art was the only form in which anything productive and interesting could happen, given what I was trying to work with. Two of my pieces have been long durational; however, most of my other work is not. I consider myself an artist who works in many different mediums, but for Mattress Performance and Self-Portrait, long durational performance art was the best way to convey my ideas.

All of my work falls under the umbrella of relational aesthetics, which, the way I understand it, includes not just the performance or the objects in the room, but also all the audience reactions to the performance and the objects. Framing things that way changes the way the audience engages with your work. The mattress performance was kind of a crash course in relational aesthetics when I saw how much it took off on the internet, more than it even took off on the ground. So in a way, the technology is unavoidable, because everything, at a certain point, is going to get reproduced for the internet.

The parameters of Mattress Performance. Credit Emma Sulkowicz.

OW: What influences led you to start creating these more experimental kinds of art? And what is your current process like?

ES: I would have to point to a specific moment in time when I went to the Yale Norfolk Residency. You know, when you’re a student, you make a certain type of work that you’re assigned to make, whereas when I went to this residency, and I was so fortunate to be able to do that at such a young age, we were encouraged to make really anything we wanted. That was my first taste of what it’s actually like to be an artist, because once you leave school, no one’s ever going to give you an assignment again. So being in the residency and having all this freedom to make whatever I wanted led me to explore new forms.

When I’m working on a project, I do research. For example, right now I’m working on a piece that would take the form of a fake doctor’s office that would be open for a month. In some respects, I started getting interested in it when I read Derrida’s writings on hospitality. From there, I figure out what I have to read next. Maybe I have to refresh my Lacan, or I have to revisit a Freud essay. One thing leads to another, and throughout my readings, I’m picking up material to use for my art.

And sometimes I find inspiration from more concrete objects or experiences. I did this one piece recently where I saw advertising on the subway for the Alberto Burri show at the Guggenheim that made me really angry, so within the same week I made a counter advertisement of my own and installed it on the subway. I didn’t need any theory for that. It just comes from an impulse. I see something, it either upsets me or gets me excited for some reason, and then I decide how to engage with it. I think that I speak most clearly through my art, so it just sort of naturally comes out as an art piece, rather than, say, an essay.

“I was really interested in the idea that every human being is performing all the time, whether it’s to another person or for themself. ”

OW: Your recent piece in LA spoke to how you are perceived and mediated. And a lot of your other work is in public space and is very engaged with the real world. So how do you view the relationship between reality and performance?

ES: I think that when I began Mattress Performance, I really thought there was a distinction between when you’re performing and when you’re living, and I worked really hard to delineate the two. But whenever I see some sort of binary forming, I try to break it down, so in Self-Portrait, my goal was to perform as my usual self on the platform. I was really interested in the idea that every human being is performing all the time, whether it’s to another person or for themself. I was interested in how people would—because I was on a platform in a gallery—treat me differently from how I expect they would have treated me had we met somewhere else, like at a party. They approached me differently simply because I was in a different space, in a different context—when my assignment, on the other hand, was just to act normally.

I mean, if the person I was talking to was pissing me off, I’d be very blunt with them, and if the person was being really nice and I enjoyed the conversation, I would engage with just as much excitement as I would normally. I wasn’t changing the way I acted because I was in a gallery. Other people assumed that I would be, because most people really believe in this distinction between art and life, but I’m trying to break down that distinction.

Self-Portrait. Credit JK Russ.

OW: Do think that the piece was successful? And how do you define success in your work?

ES: Yes. I learned a lot from it. I saw how some people would come in and really engage with the piece, and would leave feeling like they’d learned something, too, whereas other people would not be willing to give themselves over to the piece, and would then come away from it not having gained anything. For example, this one guy, who was a professor somewhere, came in, sat down on the platform across from me, and just decided it was his time to give me sort of an artful critique. However, he seemed to know nothing about political performance art. You know, I’m really excited to talk to people no matter how much reading they’ve done, but it’s frustrating when they’re then going to feel entitled to educate me on their beliefs, when I haven’t asked them to educate me. His combative mode of conversation was really off-putting. I explained why he was wrong, and I think he left feeling not so great about the piece. Overall, I think everyone’s reactions to the piece were so dependent on how they entered the room. This guy decided that he wanted to have an argument with me, so he left with kind of a sour taste in his mouth. But people who came in wanting to have fun or something like that tended to leave feeling happy. It was full of nuance and different for every person.

I definitely had envisioned it initially as a piece in which I’d show people that I’m human and not this robot they think I am, but as the piece evolved, I realized that actually there was something else going on. A lot of people came not because they wanted to engage with this game of “Is it Emma or Emmatron?” but because they had an agenda for something they wanted to tell me or something they wanted to give me…I can’t even tell you how many people brought gifts. A lot of people brought gifts as if they were offerings, a lot of people cried. That’s not really engaging with the artwork as I set it up, but I realized that everyone had their own agenda for coming.

OW: Mattress Performance was centered around an object that carried a symbolic meaning you and others put on it. Did you consider the mattress a magical object?

ES: I certainly did not, but I think other people did. Marcel Mauss’ A General Theory of Magic is a really interesting book to me. One exercise you can do with that book is actually replacing the word “magician” with “artist” every time it comes up. I think that you can really understand why people might consider the mattress a magical object when you read that book that way.

People would come up to me and say “You know, I’ve been sitting in the middle of campus all day, waiting for you to walk by, so that I can help you carry that.” And I was so surprised. Because to me, at that point…the mattress was dirty. I had to wash my hands after I touched it, it was so gross, and all these people thought they were going to have some crazy transcendental experience touching it? In a certain sense, that does mean it was magical, because if it made people feel a certain way when they touched it, then sure, I guess it worked a kind of magic. But from my perspective, we were really all just touching this dirty rectangle thing.

The sign of the mattress functions on two levels. There’s the purely symbolic level, which bears all this meaning, and perhaps magic, and then there’s the level at which it could have been any mattress. It’s just another object.

“Once a large number of people believe that this magical thing happened, who’s to say that it didn’t happen? ”

OW: What do you see as the purpose of participation in your work?

ES: What I took away from Marcel Mauss’ book is that magic works because people believe in it. There’s an old example in the book, which is Moses at the rock producing water in front of the people of Israel, and Mauss says “…while Moses may have felt some doubts, Israel certainly did not.” Once a large number of people believe that this magical thing happened, who’s to say that it didn’t happen? So, if I didn’t have participants, there would be no magic. And if art is very similar to magic, then there would be no art.

OW: At Odyssey Works, we try to cultivate an inner journey for our participant. Did you feel that Mattress Performance was transformative in this way for you and for those witnessing it?

ES: It was extremely transformative for me. The final product was something entirely different from what I had planned, and it was amazing to see how it took on a life of its own. I am not sure if people were immediately transformed upon seeing the performance in person. However, if we are to believe that it transformed the discourse on sexual assault, it must have been transformative for others. At least, I hope it was.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.

On the Art of Relevance

TODD SHALOM ON POETIC DECISION-MAKING

Todd Shalom. Credit Todd Shalom.

TODD SHALOM works with text, sound, and image to recontextualize the body in space with the vocabulary of the everyday. He is the founder and director of Elastic City, a nonprofit participatory walk organization. Elastic City makes its audience active participants in an ongoing poetic exchange with the places we live in and visit. Shalom leads walks alone and in collaboration with other artists, and works with artists in different disciplines to adapt their expertise to the participatory walk format. Walks use sensory-based techniques, reinvented folk rituals, and other exercises to investigate and intervene in the daily life of the city, its variously defined communities, and its identity politics.

“We already have everything that we need, so it’s just a question of reframing.”

Odyssey Works: You talk about framing and the way that you direct people to essentially draw a line around a thing to be beheld—and there’s some kind of magic action that happens when you draw that line. It’s an action upon attention, on the way we see. How does that magic action inform your work writ large?

Todd Shalom: The framing is a prompt I give on a walk in which I say that one person’s going to make a composition with their fingers, drawing a frame, and the other person’s going to name that composition.

Each artist comes to a walk with different things that they can offer, given their practice, and we’re really hoping to shape the participants' relationships to the group and themselves and the neighborhood in a new light. We already have everything that we need, so it’s just a question of reframing.

If we choose to use props, they’re generally very purposeful. Really, everything is purposeful on a walk. For example, the route—how we get from here to there—is just as important as what we do when someone gives a prompt at a spot where we’re all standing. The route is part of the walk. The walk is not about a thing, the walk is the thing. The walk is the performance.

Ideally by Todd Shalom and Niegel Smith. Credit Kate Glicksberg.

OW: What constitutes good in that moment? What constitutes effective? What constitutes where you’re trying to go?

TS: First, I want to make sure that the prompts are poetic, that they’re clear and concise, and that they give just enough information and boundaries to direct someone to do something, while still giving them space to dream. I think if you’re super specific, it can be really limiting, and someone can really shut down and not open up to the prompt. And if you’re too open, it’s overwhelming. I think there should be a balance.

In rehearsals, I’m always imagining the worst possible participant, and this is someone I love playing. I play the person who reacts against the prompt, who doesn’t want to follow it, who takes someone’s words and twists them into the disruptive or obnoxious.

A good prompt can really hinge on a keyword. If I say "box" instead of "frame," or if I say we’re going to make a “thing” instead of a “composition,” it changes the prompt. It’s good if people are participating, period. But it’s not great. I want more than that, so I change and tweak the prompts. The person leading the walk has so much agency, and I think that I really like to be in a spot where I feel comfortable enough to give that agency back. But again, if you give too much control to the group, the whole thing could kind of fall apart.

If the prompt is good enough, I think that it will get people to see the poetry in the words, and they’ll come up with new meanings. In one sense, this whole project has been about taking poetry off the page. So when people are thinking about the prompts in a poetic way, then I think the walk has been successful.

“All the decisions that are within our control have the potential to be poetic ones.”

OW: Tell us about your journey from poetry to your work with Elastic City.

TS: What I’m really interested in is what I call "poetic decision-making." All the decisions that are within our control have the potential to be poetic ones. What one names the file on their desktop, what one chooses to wear today, what route one takes—these are opportunities. In my work, I really want to bring forth these opportunities. Beauty or wonder or sorrow or nostalgia can be aspects of the decision-making process. So I think that everyone is in that way an artist, you know. Whether or not they’re making compelling work is for someone else to judge, but I think my work seeks to foreground the opportunities we have in our decision-making.

After studying poetry for a while, I felt dissatisfied with it. I just didn’t feel like poetry on the page was the best way in which I could express what I wanted to. And the performance of poetry felt limited, because I would have to read a poem aloud a bunch of times for someone to be able to get underneath it. I thought there had to be something else.

I’d always been interested in sound, and especially in how I could combine text and sound. Then I took some courses at Mills College, and someone told me to check out the work of Robert Ashley, and so I did. Then he was on the cover of The Wire, the UK music magazine, and the article following the feature on him was about acoustic ecology, which is the study of sonic environments. It was as if, all of a sudden, I’d found poetics in sound that were gorgeous and accessible. It didn’t seem wrapped in academic jargon. It was something I could easily get into. I especially loved the idea of soundwalks, walks that focus on listening to the soundscape around you. That's what gave me a way into this form. But I felt that the silent soundwalks with maybe some prompts given at the very beginning were a little too purist and a little too boring to me. While that serves a purpose as an academic exercise, I felt like there could be so much more engagement.

I started using a bunch of soundwalk prompts from an acoustic ecology handbook I found in the Mills library. Then I started to create my own. And then I got sick of giving soundwalks, because I’d been giving them for almost five years, and I started to wonder what else I could incorporate into the form. And I knew poetry, so I realized I could play with text, or maybe make a visual poem. Then I thought, “How can other artists work in this form?” At this point, I knew the walk form. I knew how to get people to participate. So I decided to find artists and work with them to take their knowledge in a given discipline and adapt that to the walk form. In the process, I’ve learned so many different ways of experiencing a place—from designers, therapists, photographers, choreographers—all these different artists. My experiences of many places, but especially of New York, are so layered now. For example, I can tell you what kind of sound a specific manhole cover is going to make when a car goes over it. I have this really weird knowledge of the city now, combined with memories from all these walks and personal memories. It’s saturating.

OW: How does the idea of personal or collective histories being part of the space inform the work?

TS: I gave Lucky Walk with Juan Betancurth, and we went near where I used to live on 15th and 6th. We looked around and gleaned text from the signage we saw on the street, and then we performed our text in chorus, almost like a Jackson Mac Low poem. My own personal history is definitely built into the walks, especially into why I may create a given walk. But it's more important to me to make room for a participant's experience.

OW: There’s an idea that to be participatory means to be democratic in some way. If you’re literally and figuratively guiding the participants in one direction or another, do you think that’s still true in the case of what you do, or does it not really apply?

TS: Well, I don’t necessarily think it’s democratic, but the participants are co-creators of the work. They complete the work. Since I use the trope of a walking tour, people are looking to be led. And people are already participating without realizing it, just by walking, so that’s a nice thing that's built in. I’m facilitating, essentially. Everyone is given the option of not participating if they don’t want to. No one is being forced. (And we don’t use blindfolds, for instance, because I think that’s dangerous, especially in the city. It doesn’t allow you control if you need it in a split second, which you may. You may need to see because a bus is coming, who knows.) There’s no control over someone, there are just offerings. It’s up to the individual whether or not to accept them. But if no one goes on the walk, I’m giving prompts to no one, so we do need people to be on the walk.

I don’t think I’d call my work truly democratic, because that would imply total shared authorship, or maybe consensus, and that’s not it. I feel like when I’ve experimented with that, it's felt good, because everyone was involved in the decision-making, but aesthetically, I wasn't usually so pleased with the results. You often end up with a lowest common denominator aesthetic. I want to give some agency or authority back, but I don’t want to give it all over. I think it’s important to lead or facilitate, and it’s just a question of to what degree at a given moment.

Fabstractions by Todd Shalom. Credit Nick Robles.

OW: Can you demonstrate what a prompt for this space might look like?

TS: Well, there’s a fountain here, and it’s not being activated. The obvious thing that comes to my mind is to throw a coin in there and make a wish. The other thing would be maybe to blow a wish into the fountain, so that you could see a ripple on the water. There’s something about a wish. When I see a fountain, I want to make a wish. Or, since the fountain’s not currently moving, perhaps it’s more melancholic. Maybe it’s a moment to think about someone who’s died, and place all of that in that bird that’s resting there. Our prompt can be, "If the bird were to fly away and travel with a message to someone who’s died, who would that message be to, and what would that message be?Take a minute or two, construct that message, and silently send it to the bird to deliver. We will not share these messages with the others who are seated here.”

...................

Interview by Abe Burrickson and Ana Freeman. Adapted from the live interview by Ana Freeman.

On Wonder (A Review)

Leanne Zacharias on Preventing Passivity

Credit Kevin Bertram.

LEANNE ZACHARIAS is a Canadian cellist, interdisciplinary artist, and performance curator. She has been breaking ground in the post-classical music landscape since the 90s, in collaboration with artists of all stripes. Zacharias' ongoing performance project Music for Spaces reimagines concert, public, and natural spaces with sound. Other notable work includes CityWide, which consisted of simultaneous recitals by 50 cellists to open the International Cello Festival, and Sonus Loci, a winter sound installation on Winnipeg’s frozen Assiniboine River. Her cello performance formed the climax of Odyssey Works' piece for Rick Moody, When I Left the House It Was Still Dark.

“A performance works best when everyone feels they are contributing. ”

Odyssey Works: How do you understand immersivity and interactivity? How do they work and what is the point?

Leanne Zacharias: The point is to prevent anyone, audience member or performer, from operating in anything resembling a passive or inconsequential mode. A performance works best when everyone feels they are contributing—via navigation, work, or some form of interaction.

OW: Why create experiences?

LZ: Experiences do more than most performances. They are lived rather than witnessed, so they exist differently in the memory. I think the best art is of this nature. As a performer, the task of creating an experience for someone shifts the intention from self-satisfactory pursuit to gift-giving. In giving a gift to someone, you ask different questions: What do they need? What do they want? What would they like?

OW: What are you trying to do with your work?

LZ: To enable close encounters with live performance, sound, and other people. To create musical scenarios that engage both listeners and players in a more direct way than typical concert settings do. To enhance awareness of gesture, place, and time. To ask what the audience would like that they don't know of yet.

Credit Kevin Bertram.

OW: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

In many concerts and performance situations, there's little to no collaboration between artist and audience. There's an agreement on the terms, often in the form of a transaction: audience pays admission fee, artist delivers a program. This agreement is a contract and playbook. It outlines expectations. To me, the most interesting place to find the artwork is at the explosion of that transaction—the moment when the audience realizes they're being offered a different type of contract, a new playbook with unorthodox or unclear terms.

“A heightened sensitivity to space, surroundings, and people invites elements of surprise and risk; it requires and builds trust, and creates an exciting tension that is integral to great performance.”

OW: What is the role of wonder and discovery in your work?

LZ: Crucial. If the work is a musical composition, the performer's role is interpretative. Even if a piece has been performed dozens or hundreds of times, it must be made new—through interpretive decisions, its placement in proximity to other musical works, its placement in the environment, or the placement of the performers and audience. Ideally, everyone is experiencing the discovery of a new interpretation of the piece together, in real time. I think of the entire performance, not just the music, as the work, so I attend to all the details: musical landscape, physical landscape, movement, proximity. A heightened sensitivity to space, surroundings, and people invites elements of surprise and risk; it requires and builds trust, and creates an exciting tension that is integral to great performance.

Credit Katalin Hausel.