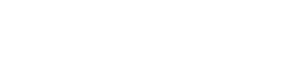

Credit Chloë Bass.

Chloë Bass is a conceptual artist working in the co-creation of performance, situation, publication, and installation. She's recently returned to Brooklyn after a summer making work in such places as Greensboro, New Orleans, St. Louis, and rural Nebraska. Chloë is a visiting assistant professor in social practice and sculpture at Queens College, CUNY. She is sometimes a collaborator, sometimes published on Hyperallergic, and adamantly and always a New Yorker. You can learn more about her at chloebass.com.

“The world is something that we make together. ”

Odyssey Works: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

Chloë Bass: The world is something that we make together. (Joseph Beuys even called the world a collaborative artwork.) There are a million tiny gestures that go into the fabrication, presentation, and maintenance of art, not to mention society. We are not always equal players; equality may be rare, or even impossible. I have no problem being an authorial voice, a game-maker, an editor, a social designer, or a leader. But I think what we forget is that these positions, except in extreme fascist cases, actually require the participation of others. My work is a series of experiences for people. It exists in the moments where it’s happening, in the echoes my participants take with them, and in the ways they and I find to share some element of what occurred with those not present.

OW: Your work often relies on relationships or interactions between two people. How does intimacy play a role in what you create?

CB: I’m actually scaling up. I’m going gradually, so I think it’s pretty hard to tell at the moment. From 2011 to 2013 I worked at the scale of the self, and produced The Bureau of Self-Recognition, a conceptual performance and installation project designed to track the process of self-recognition and its myriad outcomes. Since the beginning of 2015, I’ve been working on The Book of Everyday Instruction, which explores on-on-one social interaction. I have some exciting ideas for the next phase after that. I don’t want to say too much at the moment, but I’m looking to work with family-sized groups, and I want to make a film.

I’m preparing myself to tackle groups of people the size of entire cities, eventually. The artist Elisabeth Smolarz came to visit me in my studio a few months ago, and she joked that the ultimate manifestation of my practice would be to become president so I could do a project with the entire country. I'm learning alongside my work. I am genuinely teaching myself about the world through these artistic actions, interventions, and experiences.

I'm not necessarily an extroverted person. I think I really thrive in the depth of the magical space that can be created between two people—until one of them has to get up and go to the bathroom, and the moment breaks, and they’re back to being their regular, awkward selves in the world. I like the connection and the breakage, to be honest. I think there’s a lot of power and material in both.

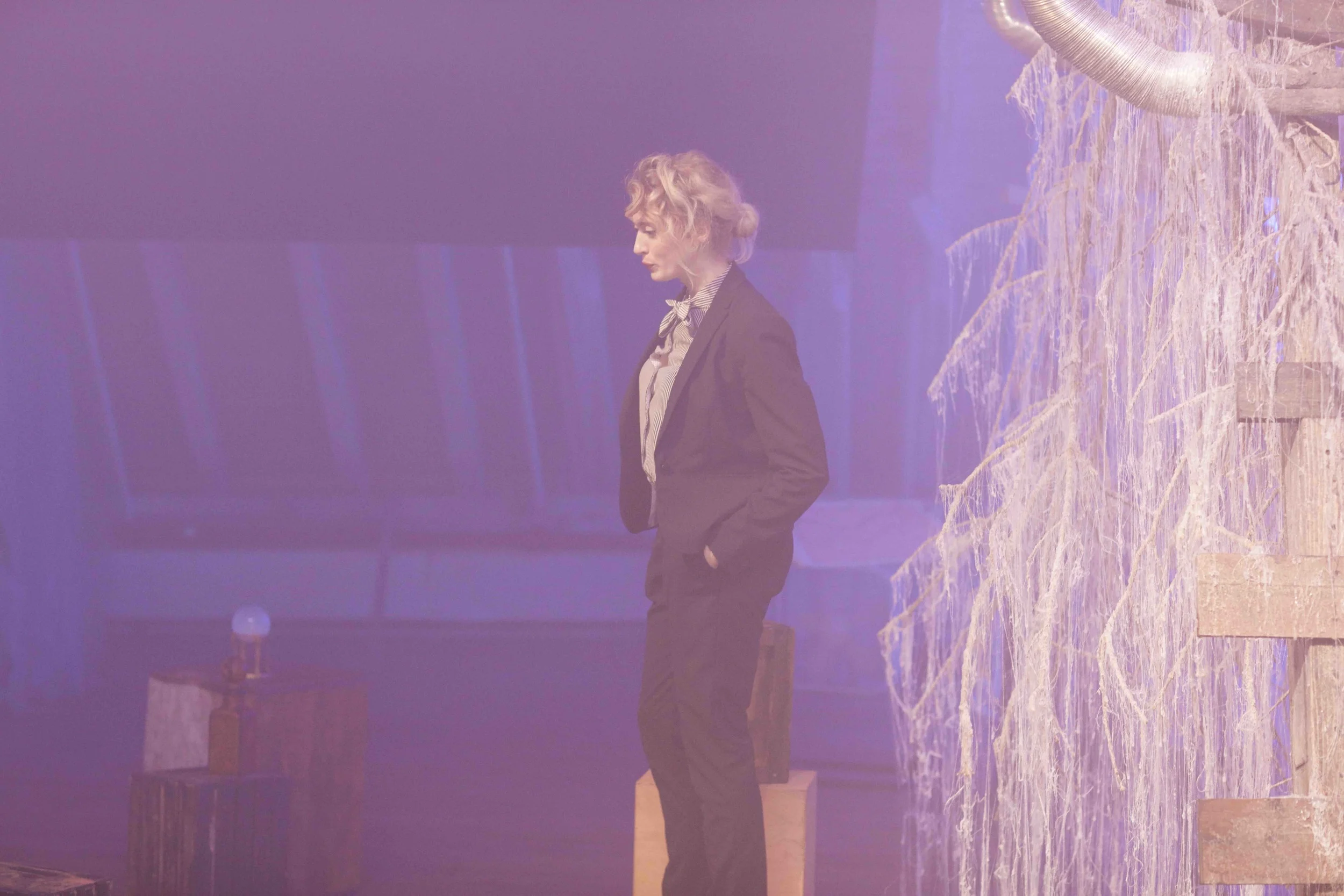

It's amazing we don't have more fights, participatory performative workshop, 2016. Credit Manuel Molina Martagon and The Museum of Modern Art.

But I want the breakage in my practice to be a conscious choice. Can we maintain the intimacy of the pair at the scale of a city? What remains, and what is lost? How can I hold people, and when is it informative to let go?

I wonder often about incorrect intimacy, and the special space it creates. I was in Cleveland for two months in 2015 spending time with strangers, joining them in their daily lives. A large part of this project turned out to be getting in the car with strangers, something we’re told not to do from the time we’re very young. There was something about beginning with an “incorrect” gesture that made my participants and I responsible to one another. Changing the usual circumstances of how and where we meet people brought us into a different kind of social and aesthetic world. Doing things wrong can hold high imaginative potential.

Recently, I was in St. Louis, where I talked to people about safety and safe places. For me, taking a stranger to a safe place and having a conversation about safety is really odd and anxiety-provoking. It’s essential to make sure that the best parts of that oddness are preserved and turned into something productive. At the same time, I have to work hard to make myself extra comfortable for the person who’s allowing for this vulnerable interaction to happen. Balancing these kinds of dynamics is a huge part of my craft.

OW: How do you understand immersivity and interactivity? How do they work and why do you use them?

CB: Well, those are the materials of life! Every experience that I have in my daily life is, to some extent, unavoidable. I might willingly choose to enter a situation, but what happens once I’ve entered it is just the product of being there.

That said, people can occupy the same space and have entirely different lived experiences. I feel a little bit suspicious about immersivity right now. What does it really mean to be immersed in anything other than your own subjectivity? How can we extend the bounds of the personal in order to improve our treatment of others? I am not speaking of empathy, which does the work of making us all affectively the same, but of a certain kind of non-understanding that teaches us we need to do better.

“Form is a kind of stitching, a way of putting a temporary experience into a more permanent shell. ”

OW: How does the social component of your work relate to the material forms you create? How do you categorize your work?

There was a time when I used to edit my artist's statement to rename myself as the type of artist I had most recently been called by others. If a review came out and said I was a performance artist, then I would call myself that. I did this not out of inherent resistance to categorization, but because I felt really new to making my own work, and was just as willing to trust others to name it as I was to trust myself.

Now I teach social practice in the art department at Queens College, and there are so many people who call me a social practice artist. From an academic and art historical perspective, I have to say that I’m not so sure they’re right. I think social practice is best described as a series of tactics that’s been culled from many fields: anthropology, sociology, psychology, community organizing, trauma studies, journalism, and, yes, art. I can only classify some of my own projects in this category. But I am an artist who works with people, that much is certain.

My current statement says that I’m a conceptual artist working in a variety of forms: situation, installation, publication. Naming myself a conceptual artist has made it ok to be making work that exists in service of a series of related ideas, rather than a series of related material practices. Form is a kind of stitching, a way of putting a temporary experience into a more permanent shell. However, the shell is really just a reminder that something has happened.

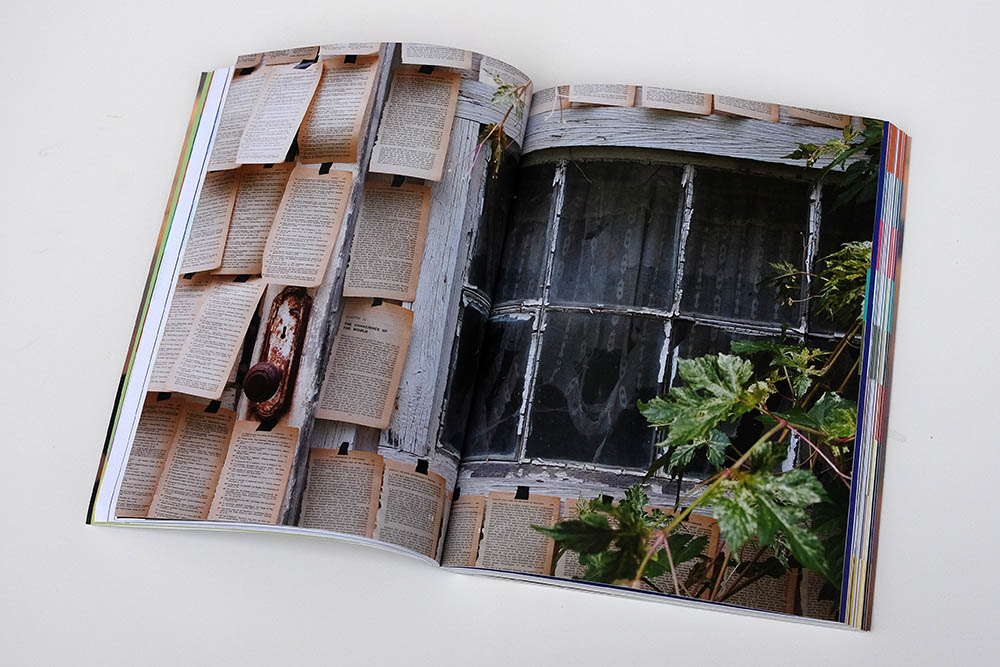

Hand-stamped cocktail napkin from Linger Longer Toast, a participatory public performance that took place in 2014. Credit Chloë Bass.

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience of art that transformed you?

CB: When I was about eight, the Guggenheim had a retrospective of Rebecca Horn’s work on view. In the museum’s oculus, Horn had hung a grand piano, which “exploded” a set number of times per hour: keys and hammers appeared to fly out of the instrument, accompanied by a dramatic sound. I loved how scary it was, how funny it was, and how we couldn’t avoid it. I don’t know that Horn’s work is a visual influence on what I do, but I’ll never forget that moment, or how it’s continued to shape my social and emotional responses to artworks.

I am also hugely influenced by Adrian Piper, Andrea Fraser, Claudia Rankine, Maggie Nelson, and Doug Ashford. And I’m a habitual eavesdropper and casual voyeur; I don’t intend to stop being inspired by these arguably creepy practices.

OW: What are you trying to do with your work?

My goal is both incredibly simple and insanely grandiose: I want us to live better together. Every piece of work that I make is in service of this aspiration. The experiences I make are triggers for a feeling. It’s on you to figure out what to do with that feeling, and how to use it in your relationships to others. The objects I make are souvenirs, tagged with memories that you might rediscover later. The words I offer are guidelines. But making the world? That’s yours.

...................

Interview by Ayden LeRoux and Ana Freeman.