Jim Findlay. Credit Pavol Liska.

JIM FINDLAY works across boundaries as a theatre artist, visual artist, and filmmaker. His recent work includes Vine of the Dead (2015), Dream of the Red Chamber (2014), and Botanica (2012). His video installation Meditation, created in collaboration with Ralph Lemon, was acquired by the Walker Art Center for its permanent collection in 2011. Findlay is a founding member of artists' group Collapsable Giraffe and performance space The Collapsable Hole. His work has been seen at BAM, Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, Arena Stage, A.R.T., and over 50 cities worldwide, including Berlin, Istanbul, London, Moscow, and Paris.

“We’re all here. Alone and together.

”

Odyssey Works: What are you trying to achieve with your art?

Jim Findlay: I’m just trying to achieve some art with my art. I’m pretty satisfied when I feel like I’ve done that.

Thinking of the work I make in terms of other senses of "achievement" feels like trying to change a tire with a poem—which sounds like a good way to make art, even though it’s a stupid way to change a tire.

I’m basically down with the idea that what makes art unique is its uselessness. If its use is immediately apparent, then it’s hard for it to be interesting. You have to look at a wrench for a really long time to see the poetry in it, because it’s hard to stop seeing the wrench. But if you can make something that's interesting and also quite apparently useless, then I feel like that’s something that fires up the curiosity neurons.

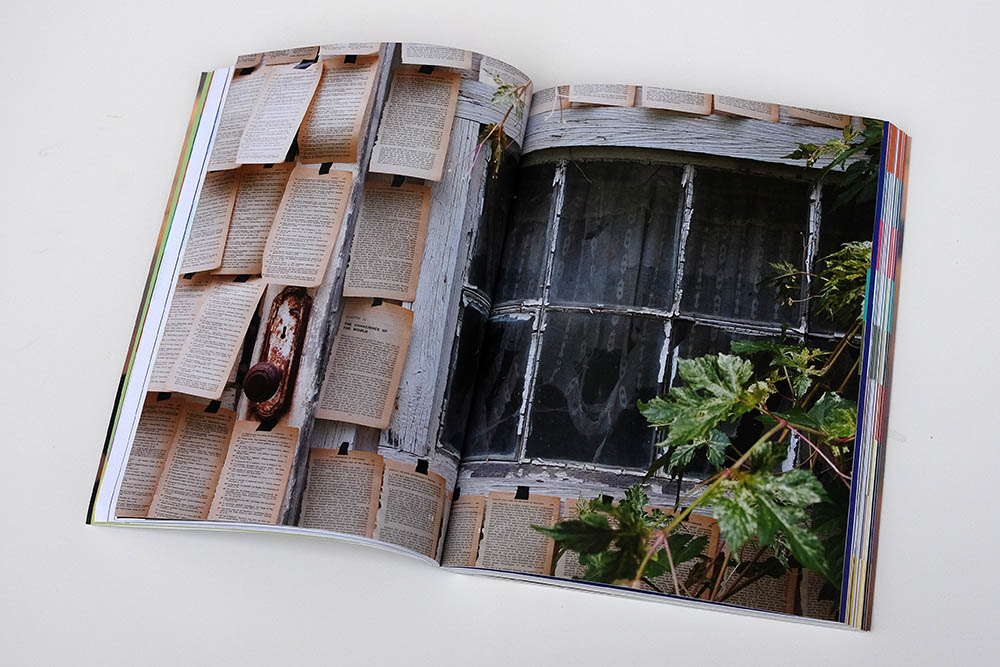

Vine of the Dead. Credit Paula Court.

OW: Why integrate multiple disciplines? What is the best way to approach this?

JF: Approach it by just diving in and using it, whatever it is. Use it wrong, use it stupidly, use it as incorrectly as possible. Don’t fall into the trap of having to understand it before you try it. It’s not about mastering something, it’s about bending it to its own special state of uselessness.

Humans are omnivores, utter generalists, pansexual, and inherently curious. We are probably one of the least specialized species on the planet. Why would we be wildly dextrous and flexible in every other aspect of our existence, but not in our art-making?

I find words and speech much more foreign than the physics of electrons and photons or the elaborate syntax of contemporary digital language. We’re living in a time of widespread visual and sonic literacy. Lay people are incredibly sophisticated about the language of the jump cut and the slow fade. Using multiple disciplines feels quite organic. I don’t think about it much. I just do it.

“I think the desire for connection and the impossibility of it pretty much sum up the whole of human experience, from the criminal to the holy.”

OW: Speaking of combining forms, your work frequently combines recorded and live performance. What is the reason behind this?

JF: It’s so much more mixed up than anyone can imagine! A lot of the media work I do is predicated on live performers using the technological medium, sometimes swimming in it. Integration of media for me means that it’s integrated into the bodies and actions of the performers. For example, in Dream of the Red Chamber, there is constant video presence in a truly epic way. But a deceptively large portion of that video is live. The technology’s main function in the world of the piece isn’t its content. Rather, its most essential function is that it occupies the performers' actions. I enjoy watching people struggle to do something difficult; using technology in performance in a rigorous way is difficult, especially when it’s largely controlled by the performers themselves.

OW: A lot of your work has an epic quality. Yet it has also been described as "intimate." This seems counterintuitive, as we usually associate intimacy in art with a more minimalist aesthetic. How can a vast scope be intimate?

JF: Creating dichotomies, tensions, and seemingly incongruous feelings is something that is very conscious in my work. And I think that we never feel more intimate to ourselves than when we feel ourselves small inside the vastness of life and the universe. There’s something about loneliness that’s not on the surface often, but that nonetheless is a strong undercurrent to everything I am. I think the desire for connection and the impossibility of it pretty much sum up the whole of human experience, from the criminal to the holy.

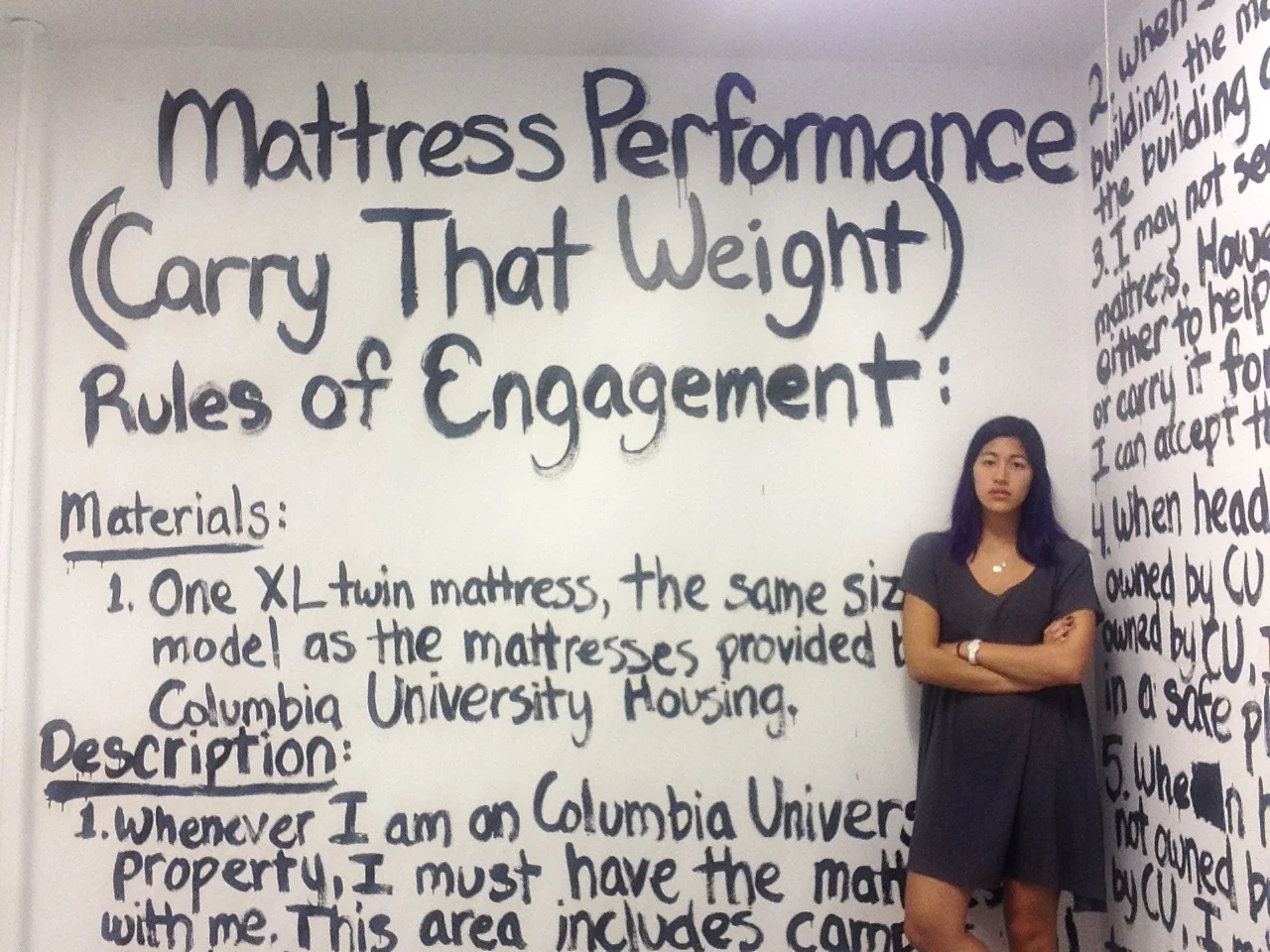

Dream of the Red Chamber. Credit Paula Court.

When I make worlds—and to me, making a piece is like making a world because it has its own set of functions and rules and features—I always want my worlds to have their own integrity. They don’t have to be realistic, or operate on the same principles as our experience, but they have to make sense on their own terms. I think that epic feeling in my work may come from my desire for a piece to have its own special autonomous feeling. I feel like the intimacy element is even more essential, and that comes from my real desire to just be there with everyone. The performers and I are not going to pretend to be other people, at least not in ways that aren’t utterly transparent, and you don’t have to pretend you’re not here either. We’re all here. Alone and together.

OW: In your performance Dream of the Red Chamber, the audience is encouraged to experience the work while drifting in and out of sleep. How does this enhance the experience? What is the connection between dreams and art?

JF: The piece makes a simple proposition: What happens when we disrupt the usual transaction between the audience and the performer? What if the audience doesn’t have to pay attention and the performer is released from their duty to entertain? Everything in the piece is in service of this proposition in some way.

“Did I make that? Did she make that? Did it happen? Does it matter? ”

I also admit that I have a lot of firsthand experience of sleeping in theaters. And I always find the haze of liminal states between being asleep and awake very pleasant. So when formulating the piece, I had a pretty good idea of the experience I was proposing to the audience.

The other aspect of this that became important for me on an aesthetic development level was that it forced me to relinquish control of the experience. A friend at the show fell asleep, and in her dream the show continued, but there was a large curtain near where she was sleeping. The performers made a big show of opening this curtain, and behind it was this very large beloved painting she had done 20 years ago that she thought had been lost forever. It was still lost in real life, but was returned in the dream. She woke up at the show crying because we had returned her painting to her, and it took her five to ten minutes to sort out what the reality was and what had been in her dream. Did I make that? Did she make that? Did it happen? Does it matter? That’s a pretty good demonstration of the connection between dreams and art, I think.

OW: Who are your influences?

JF: Captain Beefheart, La Monte Young, Elizabeth LeCompte, Reza Abdoh, Derek Jarman, Mark Twain, Kathy Acker, Werner Schroeter, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Ralph Lemon, Amy Huggans, Iver Findlay, Radiohole.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.